New findings of Brucella bacterium modifying the host immune response to continue its infectious cycle provide first-time details about how Brucella positions itself to alter immune defenses, replicate, and spread up to 72 hours after infection.

New findings of Brucella bacterium modifying the host immune response to continue its infectious cycle provide first-time details about how Brucella positions itself to alter immune defenses, replicate, and spread up to 72 hours after infection.

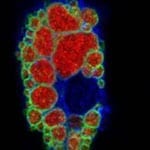

Scientists observed the Brucella bacterium in mouse and human immune cells moving to a newly identified protective compartment during a stage of infection where bacteria normally degrade and are removed. The protective compartment (shown in green on the image) only appeared in the presence of certain combinations of proteins, which the scientists were able to change for their observations. The Brucella within these compartments successfully escaped and infected adjacent cells, thus completing its lifecycle and demonstrating its capacity to subvert normal immune defenses.

Identifying the roles of host proteins required for this bacterial subversion raises new research questions and treatment ideas for Brucella and the broad field of host-microbe interactions. For example, understanding how the bacterium signals the host cell to create the protective compartments could provide scientists with strategies for blocking this process, as could the understanding of how the compartments contribute to the release of bacteria. Immune cells use the same host defense mechanism that Brucella subverts—known as autophagy—to rid themselves of many types of pathogens, including Streptococcus, Listeria, Salmonella, and Shigella. Dr. Celli’s group plans to explore further immune system evasion connections among these pathogens to better understand the mechanisms of bacterial release.

Brucella is a highly infectious bacterium of global concern which causes the disease brucellosis in animals and humans. Brucellosis is not prevalent in the United States because of decades-long eradication and surveillance programs. But in less developed countries that can’t invest in the programs, brucellosis a widespread zoonosis, an animal disease that can be transmitted to humans. The World Health Organization estimates there are 500,000 new human cases annually. Because Brucella can spread easily—and only a small dose is needed to create infection—the bacterium is considered a potential agent of bioterrorism.

The research findings, funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), were published in the Jan. 19, 2012 issue of Cell Host & Microbe, and led by Jean Celli, Ph.D., and colleagues at Washington University in St. Louis and the University of Oviedo in Spain.