Scientists are using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to obtain close-up images of the proteins that copy DNA inside the nucleus of a cell, offering new insights on how this molecular machinery works.

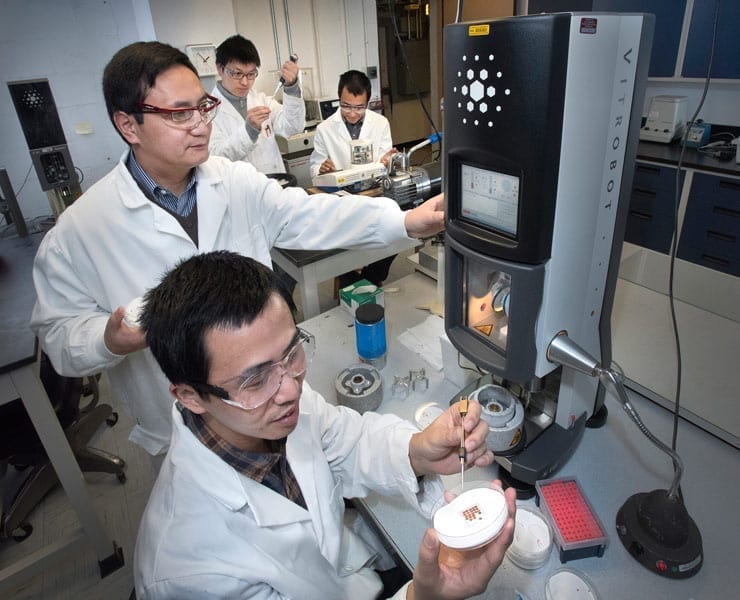

Comprised of researchers from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory, Stony Brook University, Rockefeller University, and the University of Texas, the team studied proteins from yeast cells, which share many features with the cells of complex organisms such as humans.

One advantage of using cryo-EM is that the proteins can be studied in solution, which is how they exist in the cells.

“You don’t have to produce crystals that would lock the proteins in one position,” explained Huilin Li, a biologist with a joint appointment at Brookhaven Lab and Stony Brook University and the lead author on a paper describing the new results in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. That’s important because the helicase is a molecular “machine” made of 11 connected proteins that must be flexible to work. “You have to be able to see how the molecule moves to understand its function,” Li said.

The research builds on previous work by Li and others, including last year’s collaboration with the same team that produced the first-ever images of the complete DNA-copying protein complex, called the replisome. That study revealed a surprise about the location of the DNA-copying enzymes—DNA polymerases.

This new study zooms in on the atomic-level details of the helicase portion of the protein complex—the part that encircles and splits the DNA double helix so the polymerases can synthesize two daughter strands by copying from the two separated parental strands of the “twisted ladder.”

“DNA replication is a major source of errors that can lead to cancer,” “The entire genome—all 46 chromosomes—gets replicated every few hours in dividing human cells,” Li said, “so studying the details of how this process works may help us understand how errors occur.”

Using computer software to sort out the images revealed that the helicase has two distinct conformations—one with components stacked in a compact way, and one where part of the structure is tilted relative to a more “fixed” base.

The atomic-level view allowed the scientists to map out the locations of the individual amino acids that make up the helicase complex in each conformation. Then, combining those maps with existing biochemical knowledge, they came up with a mechanism for how the helicase works.

“One part binds and releases energy from a molecule called ATP. It converts the chemical energy into a mechanical force that changes the shape of the helicase,” Li said. After kicking out the spent ATP, the helicase complex goes back to its original shape so a new ATP molecule can come in and start the process again.

“It looks and operates similar to an old style pumpjack oil rig, with one part of the protein complex forming a stable platform, and another part rocking back and forth,” Li said. Each rocking motion could nudge the DNA strands apart and move the helicase along the double helix in a linear fashion, he suggested.

This linear translocation mechanism appears to be quite different from the way helicases are thought to operate in more primitive organisms such as bacteria, where the entire complex is believed to rotate around the DNA, Li said. But there is some evidence to support the idea of linear motion, including the fact that the helicase can still function even when the ATP hydrolysis activity of some, but not all, of the components is knocked out by mutation.

“We acknowledge that this proposal may be controversial and it is not really proven at this point, but the structure gives an indication of how this protein complex works and we are trying to make sense of it,” he said.

The study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), with additional support from the Brookhaven Lab Biology Department. High-resolution cryo-EM data were collected at HHMI and the University of Texas Health Science Center.