The COVID-19 pandemic has unsurprisingly been associated with a similar epidemic of social media misinformation. But there are also some genuine clinical issues of relevance to people with existing health conditions, who are known to be more vulnerable to the disease. One particular topic that has left patients and health professionals alike confused and alarmed is the suggestion that ACE inhibitor drugs may increase the dangers of COVID-19.

First introduced in the early 1980s, ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme) inhibitors were initially used for the treatment of high blood pressure, but their role has grown over the years to include the management of heart failure, heart attacks, diabetes and kidney disease. Given that roughly one-fifth of the adult population in the UK has diagnosed hypertension, and other cardiovascular conditions are widespread, these drugs are frequently prescribed. ACE inhibitors have grown to be the third most widely prescribed drug in UK primary care and, along with their close relatives – angiotensin receptor blockers, or ARBs – they accounted for 65 million prescriptions issued in the community in 2018.

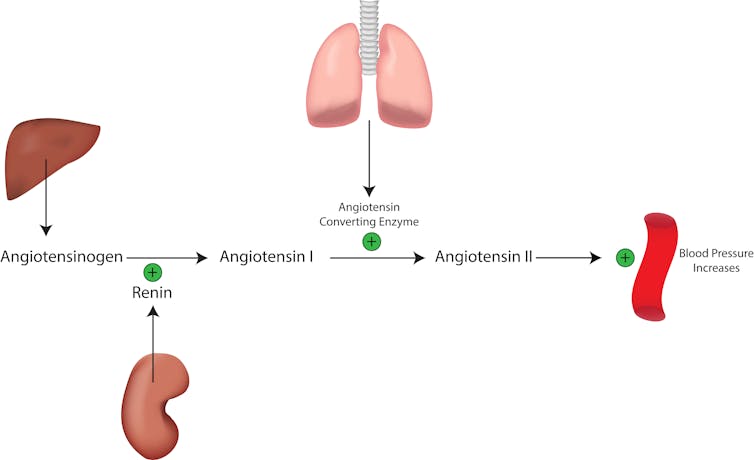

ACE inhibitors work by reducing the activity of the body’s major blood pressure regulatory mechanism, the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system. When there is reduced blood pressure in the kidney, the body produces the enzyme renin, which leads to the production of a protein called angiotensin I. This protein doesn’t have any effect on the body, but when it’s converted by another enzyme – the Angiotensin Converting Enzyme, produced particularly in the lungs – into angiotensin II, this has potent vascular effects that increase blood pressure. ACE inhibitors block this enzyme and so prevent the rise in blood pressure.

So why might this matter for COVID-19? To gain entry to human cells, a key trick employed by the coronavirus is to attach to a receptor on the surface of the cells which binds to an enzyme related to ACE, called ACE2. ACE2 has different functions to ACE, including inactivating angiotensin II.

ACE inhibitors do not appear to directly affect the action of ACE2. Nevertheless, they may have indirect effects that could lead to an increase in the number of ACE2 receptors. This has led to concerns that ACE inhibitors may facilitate COVID-19 disease, particularly as these drugs are used in older people with other health issues who we know are at risk of more severe respiratory complications.

However, the situation is not necessarily that simple. Previous work with the related condition SARS showed that reduced ACE2 (and with it, increased angiotensin II) was associated with severe lung injury. Based on this, ACE inhibitors and ARBs, by reducing angiotensin II, might actually be expected to be protective against severe lung problems. In an attempt to address these opposing theories, there is currently a clinical trial which is examining whether the ARB drug Losartan may have benefits in patients with COVID-19.

The balance of these risks and benefits is currently unknown. There is a lack of epidemiological evidence to support these drugs being either dangerous or therapeutically useful in the context of this coronavirus. One case study in China of more than 1,000 COVID-19 patients found higher rates of pre-existing cardiovascular disorders in those people with more severe viral disease, although their drug therapy was not examined. But even if one might expect ACE inhibitor or ARB use to be higher in those with cardiovascular disease, these patients are also likely to be at far higher risk of complications simply due to poor underlying cardiac, renal and respiratory function – disentangling the effects of disease and therapy requires far more study.

Many GPs are already being asked what they should do by understandably anxious patients, and are unsure of what to do themselves. Conflicting or misleading advice on social media has not helped the decision-making process. Discontinuation risks a deterioration in existing cardiovascular conditions, leading to further complications.

More research is clearly required, but in the absence of evidence to the contrary, the European Society of Cardiology put out a position statement strongly advising continuation of ACE inhibitor and ARB therapy. In the meantime, it’s essential that patients are provided with the facts as they are currently known in order for them to make the most informed decision they can about their care.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rupert Payne, Consultant Senior Lecturer in Primary Health Care, University of Bristol

This article is courtesy of The Conversation. Read the original article.