As the flu season approaches, a strained public health system may have a surprising ally — the common cold virus. Rhinovirus might also run interference against other viral epidemics.

Rhinovirus, the most frequent cause of common colds, can prevent the flu virus from infecting airways by jumpstarting the body’s antiviral defenses, researchers from report in The Lancet Microbe.

The findings help answer a mystery surrounding the 2009 H1N1 swine flu pandemic: An expected surge in swine flu cases never materialized in Europe during the fall, a period when the common cold becomes widespread.

A Yale University team led by Dr. Ellen Foxman studied three years of clinical data from more than 13,000 patients seen at Yale New Haven Hospital with symptoms of respiratory infection. The researchers found that even during months when both viruses were active, if the common cold virus was present, the flu virus was not.

“When we looked at the data, it became clear that very few people had both viruses at the same time,” said Foxman, assistant professor of laboratory medicine and immunobiology and senior author of the study.

Foxman stressed that scientists do not know whether the annual seasonal spread of the common cold virus will have a similar impact on infection rates of those exposed to the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

“It is impossible to predict how two viruses will interact without doing the research,” she said.

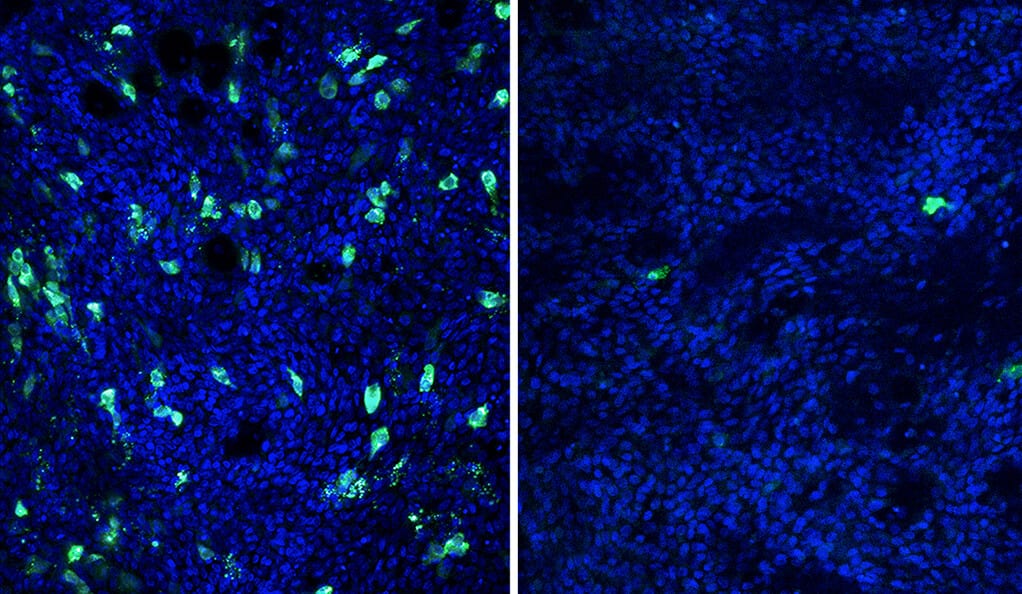

To test how the rhinovirus and the influenza virus interact, Foxman’s lab created human airway tissue from stem cells that give rise to epithelial cells, which line the airways of the lung and are a chief target of respiratory viruses. They found that after the tissue had been exposed to rhinovirus, the influenza virus was unable to infect the tissue.

“The antiviral defenses were already turned on before the flu virus arrived,” she said.

The presence of rhinovirus triggered production of the antiviral agent interferon, which is part of the early immune system response to invasion of pathogens, Foxman said.

“The effect lasted for at least five days,” she said.

Foxman said her lab has begun to study whether introduction of the cold virus before infection by the COVID-19 virus offers a similar type of protection.

The study authors note:

“The COVID-19 pandemic highlights the urgency of understanding and predicting the spread of respiratory viruses, to design effective interventions. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission is expected to intersect with the annual autumn rhinovirus epidemic and the winter influenza season in 2020–21. The work presented here raises the question as to whether rhinovirus and other respiratory viruses will interfere with SARS-CoV-2. Studies indicate that like IAV (Influenza A Virus) and many other viruses, SARS-CoV-2 is inhibited by interferons. If interference by rhinovirus disrupted the 2009 IAV epidemic in Europe, viral interference, or even therapeutic induction of the airway interferon response, might have the potential to disrupt the current pandemic. However, more work is needed to establish the effect of rhinovirus and airway interferon responses on SARS-CoV-2, especially in light of evidence that ACE2, the viral entry receptor for SARS-CoV-2, is itself an ISG (interferon-stimulated gene).”

The Foxman lab at Yale investigates the natural defense mechanisms that protect the airway from viral infections. Researchers utilize both laboratory experiments and analysis of patient samples to understand how viruses interact with the airway. Their goal is to identify mechanisms that block viral replication and to understand why these defenses don’t always work in order to find new ways to detect, prevent, and treat respiratory infections.

Interference between rhinovirus and influenza A virus: a clinical data analysis and experimental infection study. The Lancet Microbe. September 4, 2020.