In earlier days of the COVID-19 pandemic, before diagnostic testing was widely available, it was difficult for public health officials to keep track of the infection’s spread, or predict where outbreaks were likely to occur. Attempts to get ahead of the virus are still complicated by the fact that people can be infected and spread the virus even without experiencing any symptoms themselves.

When studies emerged showing that a person testing positive for COVID-19 — whether or not they were symptomatic — shed the virus in their stool, “the sewer seemed like the ‘happening’ place to look for it,” said Smruthi Karthikeyan, PhD, an environmental engineer and postdoctoral researcher at University of California San Diego School of Medicine.

From July to November 2020, Karthikeyan and team, led by Rob Knight, PhD, professor and director of the Center for Microbiome Innovation at UC San Diego, sampled sewage water to see if they could detect SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. They could. But concentrating the wastewater proved to be a bottleneck — it’s a slow and laborious multi-step process.

Now, in a paper published in mSystems, the researchers describe how they have automated wastewater concentration with the help of liquid-handling robots. They demonstrated their system’s robustness by comparing it to existing methods and showing that they can predict COVID-19 cases in San Diego by a week with excellent accuracy, and three weeks with fair accuracy, just using city sewage.

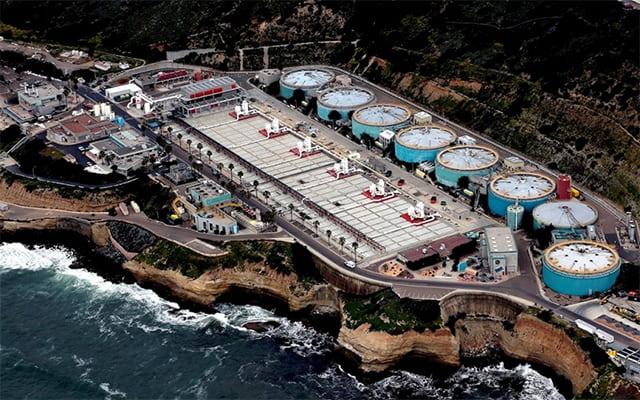

San Diego County has only one primary wastewater treatment plant, located on the coast in the city’s Point Loma neighborhood. All excrement flushed away by San Diego’s approximately 2.3 million residents, including those on the UC San Diego campus, ends up there.

Seven days a week, Karthikeyan or a colleague drove down to the treatment plant to pick up wastewater samples that had been collected and stored for them by on-site lab technicians. They brought the samples to Knight’s lab on the UC San Diego School of Medicine campus in La Jolla.

“Unfortunately, we can’t just directly test wastewater samples the way we would samples from patient nasal swabs,” Karthikeyan said. “That’s because the samples we get are highly diluted — just think of the number of people contributing to the waste stream, plus all the junk that gets flushed and makes it to the sewer system.”

Back in the lab, the researchers process the sewage using their robotic platform. The system extracts RNA — the genetic material that makes up the genomes of viruses like SARS-CoV-2 — from the samples, and runs polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to search for the virus’ signature genes. The automated, high-throughput system can process 24 samples every 40 minutes. Later the same day, Karthikeyan adds the data to a digital dashboard that tracks new positive cases.

According to Knight, the technique is faster, cheaper and more sensitive than other approaches to wastewater surveillance. The team is able to identify a single COVID-19 case in a building of approximately 500 people.

Wastewater Monitoring Key to UC San Diego’s Return to Learn Program

The researchers and students in Knight’s lab are no strangers to dealing with stool samples. The team has long been known for their studies of the gut microbiome — the unique communities of microbes that live in our gastrointestinal tracts. People all over the world participate in their research program, The Microsetta Initiative (aptly abbreviated “TMI”), by mailing their fecal swabs to Knight’s UC San Diego lab. The crowdsourced project has allowed the team to study the many factors that might influence the makeup of a person’s gut microbiome, and the many ways it influences our health.

In the spring of 2020, Knight’s team quickly pivoted their focus to look for one particular microbe: SARS-CoV-2. Soon the team formed an integral part of UC San Diego’s Return to Learn program, an evidence-based approach that has allowed the university to continue to offer on-campus housing and in-person classes and research opportunities. With approximately 10,000 students on campus, the many components of the program have kept COVID-19 case rates much lower than the surrounding community and most college campuses, maintaining a positivity rate of less than 1 percent.

Return to Learn relies on three pillars: risk mitigation, viral detection and intervention. Knight’s team and their collaborators play a big role in viral detection on campus. They help screen for the asymptomatic presence of SARS-CoV-2 in students and staff (often self-collected using test kits available from vending machines), on surfaces and in wastewater.

The team continues to collect samples daily from more than 100 wastewater samplers on the UC San Diego campus, which cover more than 300 buildings. Approximately one month after the campus detection system came online in summer 2020, a positive case was detected in the Revelle College area one Friday afternoon. The campus community was notified within 14 hours and targeted messages were sent to people associated with the affected buildings, recommending they be tested for the virus as soon as possible. More than 650 people were tested for COVID-19 that weekend.

As a result, two asymptomatic individuals were identified as being positive for COVID-19. After the campus promptly notified them, they self-isolated before an outbreak could occur. Now, wastewater screening results are available on a public dashboard and positive samples are being sequenced to track the emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variants. The Return to Learn program, including wastewater testing, has become a model for other universities, K-12 school districts and regions.

“As the barrier to entry and operate continues to drop, we hope wastewater-based epidemiology will become more widely adopted,” Knight said. “Rapid, large-scale infectious disease early alert systems could be particularly useful for community surveillance in vulnerable populations and communities with less access to diagnostic testing and fewer opportunities to distance and isolate — during this pandemic, and the next.”

Adapted from original story by Heather Buschman, PhD, UC San Diego Health