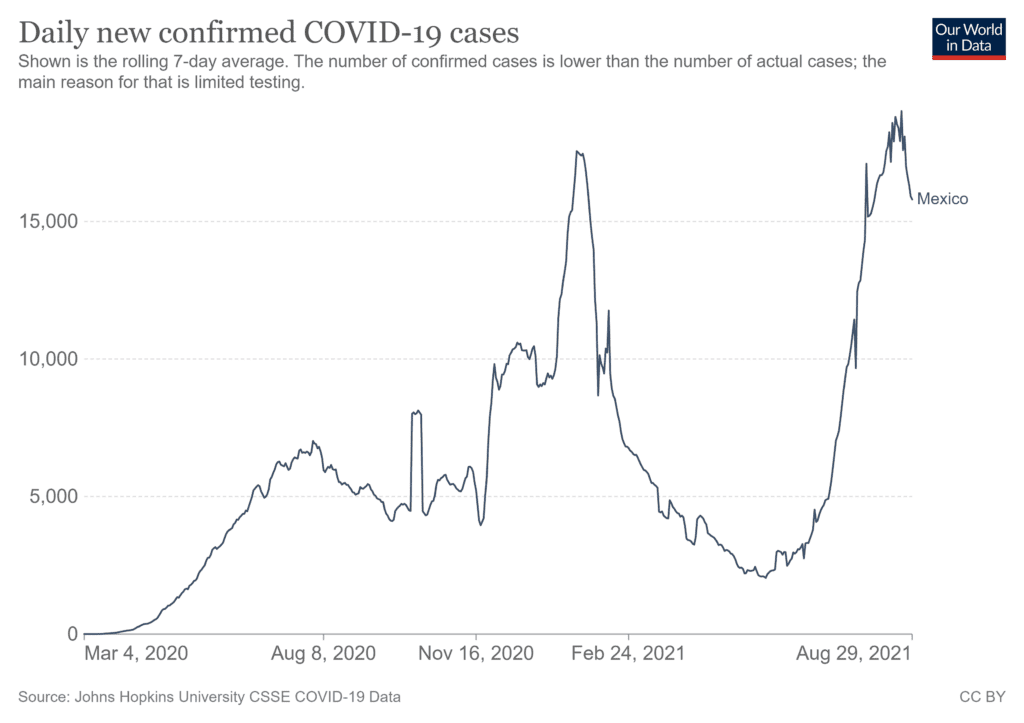

New COVID-19 cases in Mexico are approaching the highest levels seen during the second wave in late January 2021. There are now close to 22,000 cases daily, mostly in younger people – who are not yet eligible for vaccines – and other unvaccinated people. Three variants of the virus of international concern are spreading fast: alpha, gamma and delta.

Deaths remain much lower than during the peak of Mexico’s last wave. By early August 2021, more than 400 people were dying of COVID-19 in Mexico every day. That is high and rising, but back in January 2021, Mexico had about 1,300 daily deaths.

Still, with 192 deaths per 100,000 people, Mexico’s COVID-19 mortality rate is the world’s fourth highest, behind Brazil, Colombia and Argentina, which we believe is due to the Mexican government’s response and lack of sufficient precautions by the population. For comparison, the U.S. COVID-19 mortality rate is 188 deaths per 100,000 people.

Increasing but insufficient vaccinations

Vaccination coverage has been increasing since February 2021, which is helping to stem the third wave, but less than 40% of Mexico’s 128 million people have received at least one dose. Only 21% were fully inoculated against COVID-19 as of Aug. 7, 2021.

Mexico’s relatively low vaccine coverage rates are not mainly due to lack of supply – the problem that has kept the vast majority of people in low- and middle-income countries unvaccinated. Nearly 20 million of Mexico’s 91 million available doses remain unused.

Vaccine rollout has lagged because of several failures by the federal government.

One is an overall lack of federal collaboration with state and local government, and with community health organizations. Another is that President Andrés Manuel López Obrador created special COVID-19 brigades called “Roadrunner” to distribute vaccines rather than relying on Mexico´s proven, extensive and existing public health infrastructure.

The targeting of vaccines is an additional problem. Health care workers in the private sector were controversially left out of the official group-by-group vaccination rollout. And a lack of focus on the elderly meant that 24% of people over age 60 are still not fully vaccinated.

Both distribution and availability of vaccines would have to improve significantly to meet the Mexican government’s goal of vaccinating at least 70% of the country by June 2022.

Renewed pandemic restrictions

From March 2021 to July 2021, following the downward trend in infections and deaths, Mexican cities and states gradually relaxed virus containment policies such as mask-wearing and travel restrictions. However, when both infections and deaths began to spike in late July, stricter public health measures returned.

For example, in March 2021 the government allowed gatherings of up to 1,000 people, and by July gatherings were restricted to 10 people or fewer.

Mexico uses a four-colored epidemiological system to track the pandemic nationally. It determines which activities are safe to resume. A report issued on Aug. 9, 2021, shows seven of the nation’s 32 states in red status – meaning only essential activities are allowed. Nine are yellow – a moderate level of restrictions – and 15 are orange, with more stringent limitations on commercial and social activities.

Only the southern state of Chiapas is in green, allowing residents a full return to normal activities.

Lax pandemic response

Based on our analysis of the Mexican government response, we’d argue that it has not followed a robust, evidence-based public health approach to its pandemic management.

Lockdowns were late and partial. Testing, contact tracing, quarantines and isolation programs – essential elements in managing outbreaks to avoid resorting to painful and costly national shutdowns – have been minimal. Mexico has a notably low level of testing, even compared with other Latin American countries.

Such measures vary from city to city and state to state due to the absence of a coordinated, timely and rigorous national pandemic response. For example, our research found widely varying stringency of state responses that were based not on testing and the local disease burden but rather on economic and political factors.

Mexico is one of the few countries in the region with no international border-crossing policy. Travelers are allowed to pass in and out without proof of a negative test, vaccination or recent resolved infection.

National leaders have set a less-than-exemplary approach to mask use. Both the president and Mexico’s top health official have repeatedly appeared in public gatherings without a face covering.

Some state governments – like those in Guanajuato, Jalisco, Nuevo León, and Guanajuato – have stepped up in terms of implementing public health measures where federal policy is weak or absent; others have not.

Mexico had been globally recognized in the past two decades for its rigor and innovation with regard to pandemic preparedness, yet much of this system was dismantled when the López Obrador administration took office in 2019.

Learning from Mexico’s experience

We draw several policy lessons from Mexico that can help other countries determine what to do – and not do – in this and future pandemic waves.

In crises, governments must generate and disseminate reliable, credible and science-based information to encourage people to adopt appropriate mitigation measures. Studies show confusing or incorrect messages cost lives.

Our research also finds that in a decentralized federal government system like Mexico’s – or the United States’ – state and local governments are a critical part of any pandemic plan, but they need centralized, evidence-based coordination and strategic guidance from the federal government. When the federal government falls short, states make and implement their own policies. That leads to a less-than-ideal national pandemic response.

Testing, contact tracing and vaccination are the cornerstones of an effective response to the pandemic. Containment policies, or so-called “nonpharmaceutical interventions” like mask-wearing and lockdowns, can be used more sparingly when these systems are in place.

Mexico failed to apply an evidence-based, national strategy based on the above knowledge. So it has been compelled to impose strict and painful restrictions, slowing the country’s return to normalcy and damaging the economy.

A more evidence-based approach would have helped Mexico over the past 18 months, and it still can going forward.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Adolfo Martinez Valle, Head of Academic Unit, Health Public and Population Research Center, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Senior policy maker and researcher with more than 25 years of experience. As a policy maker I have designed, implemented and coordinated the evaluations of two large scale public policies: Seguro Popular, a national health insurance scheme covering nearly half of the Mexican population (50 million) and Oportunidades, a conditional transfer program, reaching nearly 25 million people living in poverty in Mexico. As a researcher, I have published nearly 50 publications as peer-reviewed articles, chapters, books, policy papers and government documents. Since 2011, I have been teaching public policy design, implemenation and evaluation as well as health system performance and health economics at the National Institute of Public Health (INSP), the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and Instituto Tecnológico de Monterrery. I am currently Head of Academic Unit at the Public Policy and Population Research Center (CIPPS) at UNAM.

Felicia Marie Knaul, Director, Institute for Advanced Study of the Americas, University of Miami. BA (International Development, University of Toronto), MA, Ph.D. (Economics, Harvard University). Knaul has dedicated more than three decades to academic, advocacy and policy work in global health focused on reducing inequities and improving the condition of vulnerable groups, primarily in low- and middle-income countries and especially in Latin America and the Caribbean. At the University of Miami, she is a Professor at the Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine, Director of the Institute for Advanced Study of the Americas, and a Full Member of the Cancer Control Program at the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center. From 2009 to 2015, Dr. Knaul was Associate Professor at Harvard Medical School and Director of the Harvard Global Equity Initiative, an inter-faculty program chaired by Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen. Her research focuses on global health, cancer, and especially breast cancer, access to pain relief and palliative care, health systems, and reform, health financing, women and health, medical employment, poverty and inequity, female labor force participation, and at-risk children and youth. She has held senior, federal government positions at the Ministries of Education and Social Development of Mexico, and the Colombian Department of Planning and worked on health reform and social development in both countries. Dr. Knaul also worked as a consultant and advisor for bilateral and multilateral agencies such as the World Health Organization and the World Bank. She has led or participated in several global policy reports, including the World Health Report 2000, and directed the production of various papers for the government of Mexico on education, health, and children´s rights. While working for the Minister of Education of Mexico she designed and implemented a thriving, national, inter-institutional program Sigamos Aprendiendo en el Hospital, and catalyzed the placement of officially-recognized schools in tertiary hospitals throughout the country. As the founder and director of the program, she put in place an inter-institutional group of government leaders, advocates, donors, and academics, working with the First Lady and the ministers of health and education. She also chaired a multi-sectorial, inter-institutional working group, and lead-authored the Programa Nacional de Acción en favor de la Infancia 2002-2010 (the national action program for children), the blueprint for the Mexican response to the Special 2012 Session of the United Nations.

This article is courtesy of The Conversation.