Science fiction is rife with fanciful tales of deadly organisms emerging from the ice and wreaking havoc on unsuspecting human victims.

From shape-shifting aliens in Antarctica, to super-parasites emerging from a thawing woolly mammoth in Siberia, to exposed permafrost in Greenland causing a viral pandemic – the concept is marvellous plot fodder.

But just how far-fetched is it? Could pathogens that were once common on Earth – but frozen for millennia in glaciers, ice caps and permafrost – emerge from the melting ice to lay waste to modern ecosystems? The potential is, in fact, quite real.

Dangers Lying in Wait

In 2003, bacteria were revived from samples taken from the bottom of an ice core drilled into an ice cap on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. The ice at that depth was more than 750,000 years old.

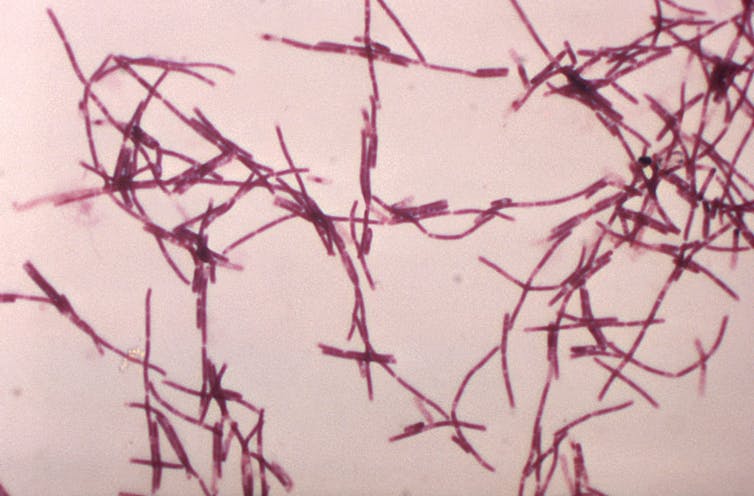

In 2014, a giant “zombie” Pithovirus sibericum virus was revived from 30,000-year-old Siberian permafrost.

And in 2016, an outbreak of anthrax (a disease caused by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis) in western Siberia was attributed to the rapid thawing of B. anthracis spores in permafrost. It killed thousands of reindeer and affected dozens of people.

More recently, scientists found remarkable genetic compatibility between viruses isolated from lake sediments in the high Arctic and potential living hosts.

Earth’s climate is warming at a spectacular rate, and up to four times faster in colder regions such as the Arctic. Estimates suggest we can expect four sextillion (4,000,000,000,000,000,000,000) microorganisms to be released from ice melt each year. This is about the same as the estimated number of stars in the universe.

However, despite the unfathomably large number of microorganisms being released from melting ice (including pathogens that can potentially infect modern species), no one has been able to estimate the risk this poses to modern ecosystems.

In a new study published today in the journal PLOS Computational Biology, we calculated the ecological risks posed by the release of unpredictable ancient viruses.

Our simulations show that 1% of simulated releases of just one dormant pathogen could cause major environmental damage and the widespread loss of host organisms around the world.

Digital Worlds

We used a software called Avida to run experiments that simulated the release of one type of ancient pathogen into modern biological communities.

We then measured the impacts of this invading pathogen on the diversity of modern host bacteria in thousands of simulations, and compared these to simulations where no invasion occurred.

The invading pathogens often survived and evolved in the simulated modern world. About 3% of the time the pathogen became dominant in the new environment, in which case they were very likely to cause losses to modern host diversity.

In the worst- (but still entirely plausible) case scenario, the invasion reduced the size of its host community by 30% when compared to controls.

The risk from this small fraction of pathogens might seem small, but keep in mind these are the results of releasing just one particular pathogen in simulated environments. With the sheer number of ancient microbes being released in the real world, such outbreaks represent a substantial danger.

Extinction and Disease

Our findings suggest this unpredictable threat which has so far been confined to science fiction could become a powerful driver of ecological change.

While we didn’t model the potential risk to humans, the fact that “time-travelling” pathogens could become established and severely degrade a host community is already worrisome.

We highlight yet another source of potential species extinction in the modern era – one which even our worst-case extinction models do not include. As a society, we need to understand the potential risks so we can prepare for them.

Notable viruses such as SARS-CoV-2, Ebola and HIV were likely transmitted to humans via contact with other animal hosts. So it is plausible that a once ice-bound virus could enter the human population via a zoonotic pathway.

While the likelihood of a pathogen emerging from melting ice and causing catastrophic extinctions is low, our results show this is no longer a fantasy for which we shouldn’t prepare.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Matthew Flinders Professor of Global Ecology and Models Theme Leader for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Flinders University. Dr. Bradshaw has a broad range of research interests including population dynamics, extinction theory, palaeo-ecology, sustainable harvest, disease ecology, human demography, climate change impacts on biodiversity, invasive species, and sustainable energy systems.

Giovanni Strona, Doctoral program supervisor, University of Helsinki. I am currently a senior researcher at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, in Ispra, Italy. I was formerly an Associate Professor in Ecological Data Sciences at the University of Helsinki, in Finland. I am a quantitative ecologist working at the interface between ecology, computer science and physics, trying to unravel the mechanisms controlling the responses of complex natural systems to the multi-faceted threats of Global Change. I am particularly interested in how the effects of diversity loss can propagate through species interaction networks, and in how co-evolutionary and ecological factors can affect this process.

This article is courtesy of The Conversation.