A newly identified virus isolated from Australian bats adds another layer of complexity to the global landscape of emerging zoonotic threats. Scientists from Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and collaborators have reported the discovery and characterization of a previously unknown henipavirus, named Salt Gully virus (SGV), in Pteropus (flying fox) bat populations in Queensland. The study was published in Emerging Infectious Diseases.

A New Player in the Henipavirus Family

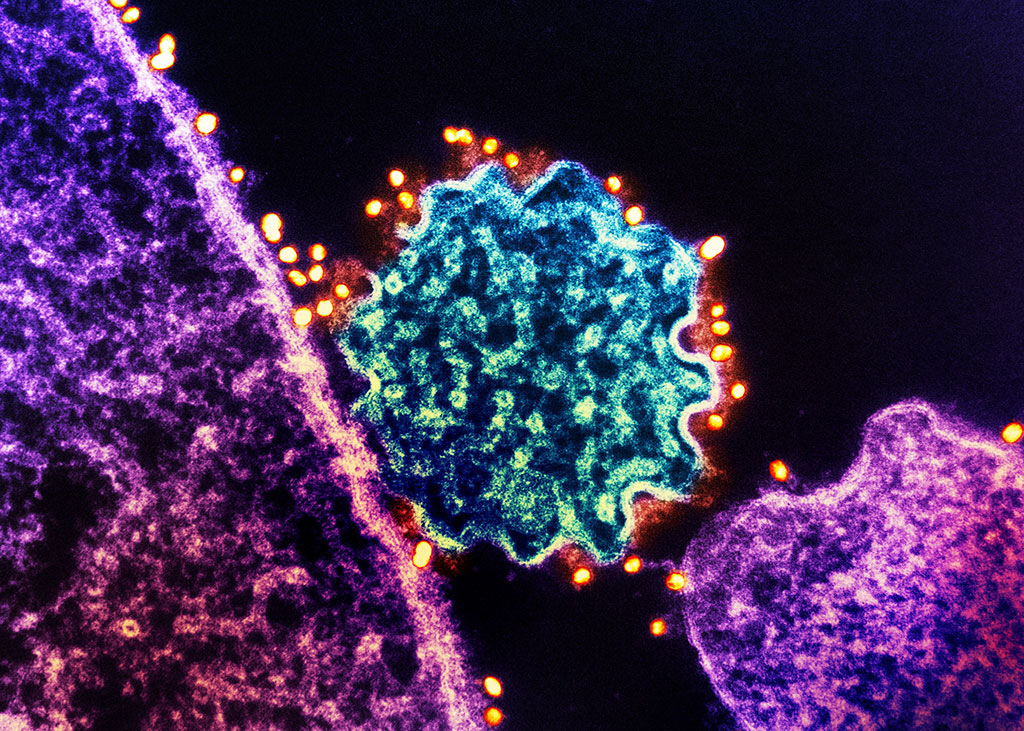

Henipaviruses—best known for Hendra virus (HeV) and Nipah virus (NiV)—are highly lethal zoonotic pathogens capable of crossing species barriers with devastating effect. Since their recognition in the 1990s, both HeV and NiV have caused fatal outbreaks in humans and animals, prompting their classification as Biosafety Level 4 (BSL-4) pathogens. Unlike these well-studied viruses, SGV was detected in bat urine collected in 2011 and only recently fully sequenced and characterized.

SGV shares 35–38% genetic identity with other known henipaviruses and is most closely related to Angavokely virus, which was identified in Madagascan fruit bats in 2022. Despite this relatedness, SGV appears to diverge in critical ways, particularly in how it enters host cells.

Infection Potential Across Species

Laboratory tests showed that SGV can infect human, bat, and monkey-derived cell lines, though with slower replication compared to Hendra virus. Interestingly, SGV did not replicate in horse or pig cells, which distinguishes it from pathogenic henipaviruses like Hendra and Nipah that cause severe disease in livestock. This narrower host range could indicate reduced spillover risk to domestic animals but underscores uncertainty about its implications for human health.

Most concerning for biosecurity stakeholders, SGV was shown to infect human epithelial cells in vitro, demonstrating that the virus has at least some capacity for cross-species transmission. The extent to which this translates into real-world pathogenicity remains unknown.

A Different Path to Cell Entry

One of the most striking findings is SGV’s independence from the ephrin-B2 and ephrin-B3 receptors, which are the well-established entry points for Hendra and Nipah viruses. Instead, SGV appears to use an as-yet unidentified receptor to gain entry into host cells. This discovery complicates efforts to anticipate the virus’s species tropism and raises questions about whether existing therapeutic or vaccine strategies that target ephrin-receptor pathways would be effective against it.

Why This Matters for Global Health Security

The emergence of SGV highlights ongoing surveillance challenges. Although bat surveillance efforts frequently detect henipa-like viruses, successful isolation and laboratory study remain rare due to technical barriers. The fact that SGV was successfully isolated and grown provides a crucial opportunity to better understand the evolutionary trajectory of henipaviruses.

For public health and biosecurity professionals, the implications are twofold:

- Surveillance: Continued bat monitoring is critical, as novel viruses are being detected across diverse host species and geographies.

- Preparedness: SGV’s ability to infect human cells but not livestock suggests a different spillover risk profile, demanding tailored research into transmission potential and countermeasures.

Looking Ahead

While no human or animal disease has yet been attributed to Salt Gully virus, its discovery underscores the unpredictability of viral emergence. Future work will need to identify the unknown receptor SGV exploits, assess its pathogenicity in animal models, and determine whether it poses a tangible risk to human populations.

As the number of novel batborne viruses identified continues to grow, the central challenge remains: distinguishing those that are benign from those with pandemic potential. SGV represents both a scientific breakthrough and a reminder of the vigilance required in the face of emerging infectious diseases.

Barr J, Caruso S, Edwards SJ, et al. Novel Henipavirus, Salt Gully Virus, Isolated from Pteropid Bats, Australia. Emerging Infectious Diseases