The World Health Organization has estimated that about 200,000 lives a year may be lost due to the use of counterfeit anti-malarial drugs. A new Oregon State University technology may be able to help address that problem by testing drugs for efficacy at a cost of a few cents.

The new test is inexpensive, simple, and can tell whether or not one of the primary drugs being used to treat malaria is genuine. When broadly implemented, this might save thousands of lives every year around the world, and similar technology could also be developed for other types of medications and diseases, experts say.

Findings on the new technology were just published in Talanta, a professional journal.

“There are laboratory methods to analyze medications such as this, but they often are not available or widely used in the developing world where malaria kills thousands of people every year,” said Vincent Remcho, a professor of chemistry and Patricia Valian Reser Faculty Scholar in the OSU College of Science, a position which helped support this work.

“What we need are inexpensive, accurate assays that can detect adulterated pharmaceuticals in the field, simple enough that anyone can use them,” Remcho said. “Our technology should provide that.”

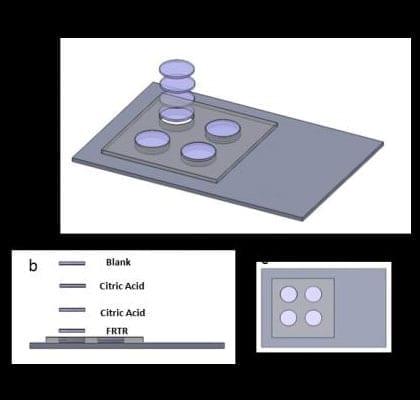

The system created at OSU looks about as simple, and is almost as cheap, as a sheet of paper. But it’s actually a highly sophisticated “colorimetric” assay that consumers could use to tell whether or not they are getting the medication they paid for – artesunate – which is by far the most important drug used to treat serious cases of malaria.

The assay also verifies that an adequate level of the drug is present.

In some places in the developing world, more than 80 percent of outlets are selling counterfeit pharmaceuticals, researchers have found. One survey found that 38-53 percent of outlets in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam had no active drug in the product that was being sold.

Artesunate, which can cost $1 to $2 per adult treatment, is considered an expensive drug by the standards of the developing world, making counterfeit drugs profitable since the disease is so prevalent.

Besides allowing thousands of needless deaths, the spread of counterfeit drugs with sub-therapeutic levels of artesunate can promote the development of new strains of multi-drug resistant malaria, with global impacts. Government officials could also use the new system as a rapid screening tool to help combat the larger problem of drug counterfeiting.

The new technology is an application of microfluidics, in this instance paper microfluidics, in which a film is impressed onto paper that can then detect the presence and level of the artesunate drug. A single pill can be crushed, dissolved in water, and when a drop of the solution is placed on the paper, it turns yellow if the drug is present. The intensity of the color indicates the level of the drug, which can be compared to a simple color chart.

OSU undergraduate and graduate students in chemistry and computer science working on this project in the Remcho lab took the system a step further, and created an app for an iPhone that could be used to measure the color, and tell with an even higher degree of accuracy both the presence and level of the drug.

The technology is similar to what can be accomplished with computers and expensive laboratory equipment, but is much simpler and less expensive. As a result, use of this approach may significantly expand in medicine, scientists said.

“This is conceptually similar to what we do with integrated circuit chips in computers, but we’re pushing fluids around instead of electrons, to reveal chemical information that’s useful to us,” Remcho said. “Chemical communication is how Mother Nature does it, and the long term applications of this approach really are mind-blowing.”

Source: Oregon State University, adapted.