The National Institutes of Health has awarded the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation (OMRF) a five-year, $14.5 million grant to continue its research on anthrax and the bacteria’s effects on humans.

For 10 years, OMRF scientist Mark Coggeshall, Ph.D. and his colleagues have studied the human immune response to anthrax bacteria as part of NIH’s Cooperative Centers for Human Immunology. The original funding came soon after anthrax-laced letters killed five and sickened 17 on the heels of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

Identifying New Anthrax Countermeasures

The long-term goal of the Cooperative Centers for Human Immunology program is to identify new vaccines and drug targets. Grants are awarded to institutions with noted expertise in the study of the human immune system. In addition to OMRF, other CCHI-funded institutes include Stanford University, Harvard University, Rockefeller University, Emory University and the University of Maryland.

“From the start, our goal has been to gain a better understanding of anthrax, especially its inhalable form,” Coggeshall said. “By the time a patient seeks medical care, antibiotics become less effective, and the toxin essentially shuts down the immune response.”

Focus on Anthrax End-State of Sepsis

With a team that includes collaborators at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center (OUHSC), the researchers have focused their work on sepsis, the blood poisoning that ultimately results from anthrax exposure.

“We identified the trigger in the bacteria that causes this pathology,” says Coggeshall. “Now we are seeking ways to override or disable it and make it less deadly.”

The new grant covers three specific projects at OMRF:

- Coggeshall will study parts of the anthrax bacteria that cause inflammation and human pathology of the disease.

- Judith James, M.D., Ph.D., will study the anthrax vaccine that is administered to US military personnel.

- Darise Farris, Ph.D., will test human components that contribute to inflammation accompanying bacterial infections.

OUHSC researcher Jordan Metcalf, Ph.D., will explore the ways in which the anthrax spores move from the lungs to the rest of the body. Jimmy Ballard, Ph.D., also at OUHSC, will identify peptides made by human immune cells that neutralize the anthrax bacteria.

All the projects are supported by scientists from core laboratories at OMRF, including Florea Lupu, Ph.D., who studies human sepsis pathology, Kenneth Smith, Ph.D., who will generate recombinant human monoclonal antibodies, and Linda Thompson, Ph.D., who will provide expertise on cell sorting and identification.

Immune Response to Anthrax Bacteria

“Historically, researchers have focused on the anthrax bacteria themselves,” said OMRF President Stephen Prescott, M.D. “OMRF scientists decided, instead, to study how the human immune system forms—or fails to form—immune responses to those bacteria. That non-traditional approach now is paying off, and this additional funding should bring about incredible advances in our approach to treating anthrax infection.”

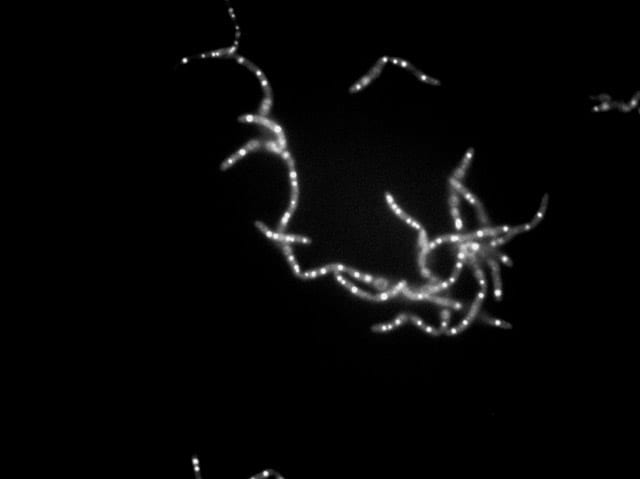

The form of anthrax used in this project, known as the Sterne strain, is not harmful to humans. This non-virulent strain is less dangerous to humans and is commonly used to vaccinate livestock against the disease.

While terror attacks with so-called weaponized anthrax are very rare, Coggeshall, who holds the Robert S. Kerr Endowed Chair in Cancer Research at OMRF, sees a wide range of other important applications that could result from these studies.

“We now have better ideas now about how anthrax works,” he said. “Even if we aren’t right about some of our ideas, the information we gain will be useful in teaching us more about other dangerous and infectious diseases caused by strep and MRSA and how to control them.”

Recent anthrax-related studies published by Coggeshall include:

- Toxin inhibition of antimicrobial factors induced by Bacillus anthracis peptidoglycan in human blood

- The sepsis model: an emerging hypothesis for the lethality of inhalation anthrax

- Bacillus anthracis peptidoglycan activates human platelets through FcγRII and complement

- Bacillus anthracis lethal toxin reduces human alveolar epithelial barrier function

Source: Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation press release, adapted.