The current method to treat acute toxin poisoning is to inject antibodies, commonly produced in animals, to neutralize the toxin. But this method has challenges ranging from safety to difficulties in developing, producing and maintaining the anti-serums in large quantities.

New research led by Charles Shoemaker, Ph.D., professor in the Department of Infectious Disease and Global Health at Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University, shows that gene therapy may offer significant advantages in prevention and treatment of botulism exposure over current methods. The findings of the National Institutes of Health funded study appear in the August 29 issue of PLOS ONE.

Shoemaker has been studying gene therapy as a novel way to treat diseases such as botulism, a rare but serious paralytic illness caused by a nerve toxin that is produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. Despite the relatively small number of botulism poisoning cases nationally, there are global concerns that the toxin can be produced easily and inexpensively for bioterrorism use. Botulism, like E. coli food poisoning and C. difficile infection, is a toxin-mediated disease, meaning it occurs from a toxin that is produced by a microbial infection.

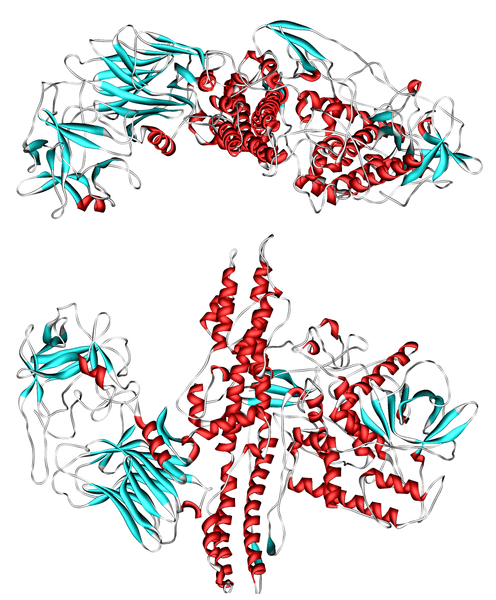

Shoemaker’s previously reported antitoxin treatments use proteins produced from the genetic material extracted from alpacas that were immunized against a toxin. Alpacas, which are members of the camelid family, produce an unusual type of antibody that is particularly useful in developing effective, inexpensive antitoxin agents.

A small piece of the camelid antibody – called a VHH – can bind to and neutralize the botulism toxin. The research team has found that linking two or more different toxin-neutralizing VHHs results in VHH-based neutralizing agents (VNAs) that have extraordinary antitoxin potency and can be produced as a single molecule in bacteria at low cost. Additionally, VNAs have a longer shelf life than traditional antibodies so they can be better stored until needed.

The newly published PLOS ONE study assessed the long-term efficacy of the therapy and demonstrated that a single gene therapy treatment led to prolonged production of VNA in blood and protected the mice from subsequent exposures to C. botulinum toxin for up to several months.

Virtually all mice pretreated with VNA gene therapy survived when exposed to a normally lethal dose of botulinum toxin administered up to nine weeks later. Approximately 40 percent survived when exposed to this toxin as late as 13 or 17 weeks post-treatment. With gene therapy the VNA genetic material is delivered to animals by a vector that induces the animals to produce their own antitoxin VNA proteins over a prolonged period of time, thus preventing illness from toxin exposures.

The second part of the study showed that mice were rapidly protected from C. botulinum toxin exposure by the same VNA gene therapy, surviving even when treated 90 minutes after the toxin exposure.

“We envision this treatment approach having a broad range of applications such as protecting military personnel from biothreat agents or protecting the public from other toxin-mediated diseases such as C. difficile and Shiga toxin-producing E. coli infections,” said Shoemaker, the paper’s senior author. “More research is being conducted with VNA gene therapy and it’s hard to deny the potential of this rapid-acting and long-lasting therapy in treating these and several other important illnesses.”

Read the study at PLOS ONE: Prolonged Prophylactic Protection from Botulism with a Single Adenovirus Treatment Promoting Serum Expression of a VHH-Based Antitoxin Protein.