Across a broad swath of the southern United States, residents face a tangible but mostly unrecognized risk of contracting Chagas disease—a stealthy parasitic infection that can lead to severe heart disease and death—according to new research presented this week at the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) Annual Meeting.

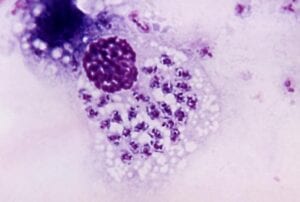

Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) is typically spread to people through the feces of blood-sucking triatomine bugs sometimes called “kissing bugs” because they feed on people’s faces during the night. The disease, which can also be spread through blood supply, affects 7 to 8 million people worldwide and can be cured—if it is caught early.

Often considered a problem only in Mexico, Central America and South America, Chagas disease is being seen in Texas and recognized at higher levels than previously believed, reported researchers from Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Among those infected are a high percentage believed to have contracted the disease within the U.S. border, according to the scientists whose findings will also be published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

“We were astonished to not only find such a high rate of individuals testing positive for Chagas in their blood, but also high rates of heart disease that appear to be Chagas-related,” said Baylor epidemiologist Melissa Nolan Garcia, one of the researchers who presented findings from a series of studies. “We’ve been working with physicians around the state to increase awareness and diagnosis of this important emerging infectious disease.”

And while this research was conducted in Texas, kissing bugs are found across half of the United States, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. Bites from these insects may be infecting people who are never diagnosed, due to a lack of awareness of Chagas disease by healthcare personnel and the U.S. healthcare system.

Chagas Often Overlooked as Risk Factor for Heart Disease

Garcia’s team conducted an analysis of routine testing of Texas blood donors for Chagas between 2008 and 2012. In that study published in Epidemiology and Infection (August 2014), the researchers found that one in every 6,500 blood donors tested positive for exposure to the parasite that causes Chagas disease. That figure is 50 times higher than the CDC’s estimated infection rate of one in 300,000 nationally, but according to Garcia, a rate that is consistent with other studies in the southern United States indicating a substantial national disease burden. Since 2007, all potential blood donors within the United States are screened for exposure to the Chagas disease parasite.

“We think of Chagas disease as a silent killer,” Garcia said. “People don’t normally feel sick, so they don’t seek medical care, but it ultimately ends up causing heart disease in about 30 percent of those who are infected.”

Symptoms can range from non-existent to severe with fever, fatigue, body aches, and serious cardiac and intestinal complications. Positive blood donors, who would likely develop chronic Chagas disease over time, could cost about US $3.8 million for health care and lost wages for those individuals, according to the researchers’ calculations. And according to a recent study published in the The Lancet Infectious Diseases, societal and healthcare costs for each infected person in the United States averages $91,531.

“We’re the first to actively follow up with positive blood donors to assess their cardiac outcomes and to determine where southeastern Texas donors may have been exposed to Chagas,” Garcia said. “We are concerned that individuals who test positive are not seeking medical care or being evaluated for treatment. And even if they do seek medical care, we heard from some patients that their primary care doctors assumed the positive test represented a ‘false positive’ due to low physician awareness of local transmission risk.”

Garcia shared the findings from separate pilot studies conducted by the Baylor team, which followed 17 Houston-area residents who were infected. They found that 41 percent of them had signs of heart disease caused by the infection, including swollen, weakened heart muscle and irregular heart rhythms caused by the parasite burrowing into heart tissue. Most of these individuals lived in rural areas or spent a significant amount of time outside. One of the individuals was an avid hunter and outdoorsman. At least six of them had insignificant travel outside the United States and they didn’t have mothers from foreign countries, indicating they had likely become infected locally in Texas.

As blood donor screening is currently the only active screening program in the United States, they provide an insight into the characteristics of who might be at risk for disease. “People who give blood are usually generally healthy adults. The people that we worry about in terms of burden of disease here are from rural settings and people who live in severe poverty. So the burden of disease may be even higher than what we see in this study,” said Kristy Murray, DVM, PhD, a co-author on the study and associate professor of tropical medicine at Baylor.

Local Kissing Bugs Spreading Disease

Kissing bugs emerge at night to feed. Once they have bitten and ingested blood, they defecate on their victim and the parasites then enter the body through breaks in the skin. While no firm data exists on how many bugs in the United States may carry the parasite, another pilot study conducted by the research team at Baylor, and presented as a poster during the ASTMH meeting, may shed some light on the issue. In that study, researchers collected a random sample of 40 kissing bugs found near homes in 11 central-southern Texas counties. They found 73 percent of the insects carried the parasite and half of the positive bugs had dined on human blood in addition to a dozen types of animals including dogs, rabbits, and raccoons.

“The high rate of infectious bugs, combined with the high rate of feeding on humans, should be a cause of concern and should prompt physicians to consider the possibility of Chagas disease in U.S. patients with heart rhythm abnormalities and no obvious underlying conditions,” said Murray.

New Analysis Uncovers Large Treatment Gap

Another ASTMH Annual Meeting presentation shows people who test positive for Chagas disease mostly go untreated. Jennifer Manne-Goehler, MD, a clinical fellow at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, collected data from the CDC and the American Association of Blood Banks and compared the almost 2,000 people who tested positive through the blood banking system to the mere 422 doses of medications administered by the CDC from 2007 to 2013.

“This highlights an enormous treatment gap,” said Manne-Goehler. “In some of the areas of the country we know there are a lot of positive blood donors, yet people still don’t get care. We don’t know what happens to them because there is no follow up.”

In the United States, most physicians are unfamiliar with the disease, and some who have heard of it mistakenly dismiss Chagas disease as a not-so-serious health concern, even in parts of the country where many people may be living with Chagas symptoms, she said at an ASTMH presentation on access to treatment. Further complicating the situation, in the United States the currently available medicines used to treat Chagas disease have not been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Physicians seeking treatment for their patients are referred to the CDC, which makes two drugs—nifurtimox and benznidazole—available, both of which carry the risk of side effects including nausea, weight loss and possible nerve damage.

In addition to data collection, Manne-Goehler conducted interviews with physicians, state health directors, and other healthcare workers treating patients diagnosed with Chagas disease in states with higher numbers of cases: Texas, California, Florida, Virginia, New York and Massachusetts. The findings revealed a disjointed, ad hoc approach to both diagnosing and treating the disease. Most of the doctors interviewed had never treated a patient whose infection had been identified through the blood donor system.

Manne-Goehler and her colleagues Michael Reich, PhD, of the Harvard School of Public Health and Veronika Wirtz PhD, of the Boston University Center for Global Health and Development, are calling for the creation of an independent expert panel to define clinical screening guidelines to help improve identification of patients with Chagas disease in the United States. In addition, they argue for creation of a physician-referral network so that physicians who are unfamiliar with the disease can send patients to providers who regularly diagnose and treat cases of Chagas disease.

Several ASTMH presenters also argued for a more comprehensive system of surveillance beyond testing of blood donors.

“So little surveillance has been done that we don’t know the true disease burden here in the United States,” said Murray. “The next step is to study populations considered high risk. There is still a lot to be learned in terms of who is contracting the disease within the United States.”