Scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found that a protein made by the Ebolavirus removes a protective coat from the virus’s genetic material, exposing the viral genome so that it can be copied, and then returns the coat.

Simply interfering with this process appears to kill the virus.

The researchers introduced proteins into Ebola-infected cells, which carried a short chain of amino acids that forms the part of the protein that removes the coat. But they lacked the ability to return the coating, disrupting the emergence of newly created viruses from infected cells. Consequently, the virus did not survive.

“This coat-check protein, known as VP35, has a great deal of potential as a new target for Ebola treatments,” said senior author Gaya Amarasinghe, PhD, assistant professor of pathology and immunology at the School of Medicine. “If we can block this process, we can stop Ebola infection by blocking viral replication.”

The study appears April 9 in Cell Reports.

“One of the major challenges was that the part of VP35 involved in this interaction is an intrinsically disordered peptide,” said Leung, an assistant professor of pathology and immunology at Washington University. “This means that it may not take on a definite structure until it binds to another protein. That made structural studies of VP35 difficult because the structure, which plays a critical role in determining function, doesn’t form without its specific binding partner.”

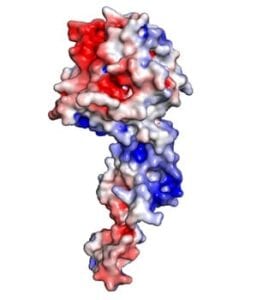

The researchers showed that VP35 binds to the virus’s nucleoprotein — which forms part of the protective coat worn by the virus’ RNA. They found that this binding removes the nucleoprotein from the viral RNA prior to replication. And while the viral RNA is being copied, VP35 keeps newly synthesized nucleoproteins from attaching to other RNA in the host cell.

New copies of the virus require new protein coats. So VP35 also ensures that new nucleoproteins — made by the host cell’s protein-making machinery — bind only to Ebola RNA, allowing the virus to complete replicating. Disabling or disrupting VP35 could stop the virus in its tracks, according to Amarasinghe.

The research was supported by grants from the U.S. Department of Defense; Defense Threat Reduction Agency; National Institutes of Health (NIH); National Institute of General Medical Sciences; and the Center for Structural Genomics of Infectious Diseases.

Read the study at Cell Reports: An intrinsically disordered peptide from Ebola virus VP35 controls viral RNA synthesis by modulating nucleoprotein-RNA interactions.

Image credit: Amarasinghe Lab