Immune cells that hang around after parasitic skin infection help ward off secondary attack, according to a new research published in The Journal of Experimental Medicine. The findings may prove to be the key to successful anti-parasite vaccines.

Leishmania are a group of parasites that are transmitted by sandflies and cause a variety of diseases, including an ulcerative skin disease. Successful clearance of Leishmania infection results in long-lasting immunity to reinfection.

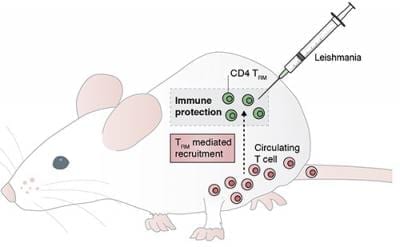

This protection relies in part on circulating immune cell called memory CD4+ T cells, which recall the initial infection and respond with increased rapidity and vigor. But the protection provided by transferring these memory cells into uninfected mice pales in comparison to that conferred by prior infection, suggesting the involvement of other cells or pathways.

Phillip Scott and his colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania now show that circulating memory CD4+ T cells rely on a little help from skin-resident friends. The group found that some of the Leishmania-fighting CD4+ T cells that help fend off initial infections in mice linger in the skin for up to a year after the infection resolves.

These skin-resident memory cells reduced the number of parasites in the skin during secondary infection, largely due to their ability to attract parasite-fighting memory CD4+ T cells from the blood.

Invoking the dual action of skin and blood memory CD4+ T cells may be the key to developing an effective anti-Leishmania vaccine for humans, which has thus far been elusive.

Read the study: Skin-resident memory CD4+ T cells enhance protection against Leishmania major infection.