Researchers from the University of Liverpool have conducted a study of Ebola survivors to determine if the virus has any specific effects on the back on the eye.

Using an ultra widefield retinal camera, a clinical research team led by Janet Scott and Calum Semple, from the University’s Institute of Translational Medicine, assessed survivors discharged from the Ebola Treatment Unit at the 34th Regiment Military Hospital in Freetown, Sierra Leone.

A total of 82 Ebola survivors who had previously reported ocular symptoms and 105 unaffected controls from civilian and military personnel underwent ophthalmic examination, including widefield retinal imaging.

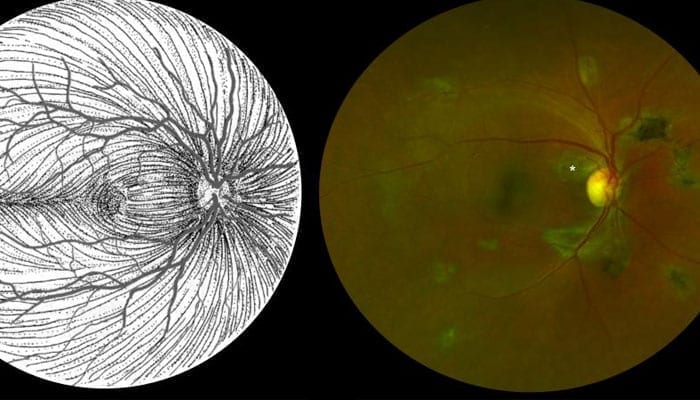

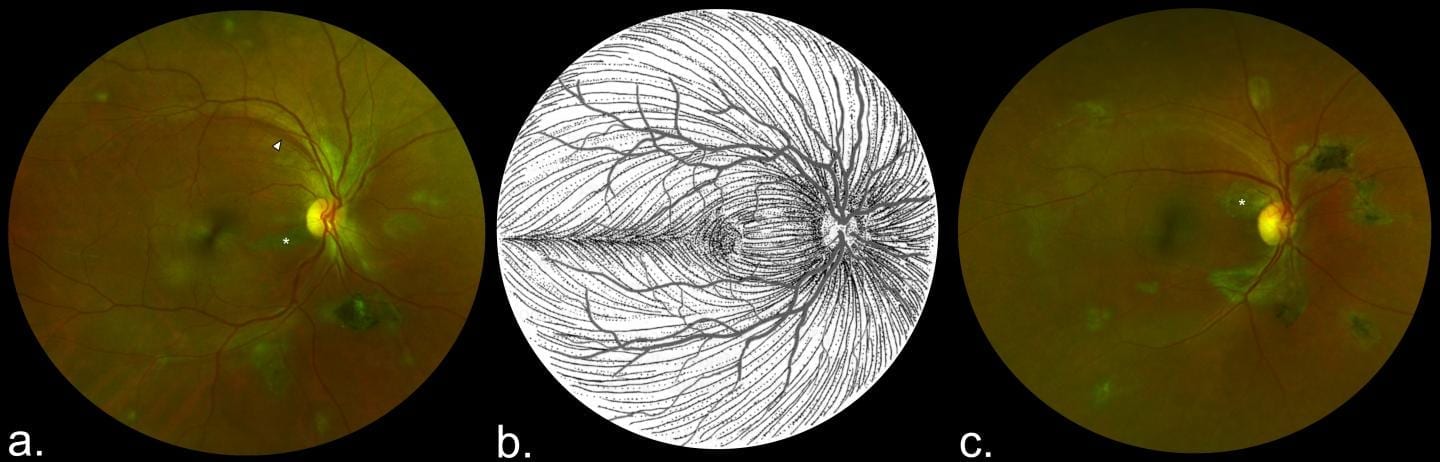

The results of the research, which has been published in the Emerging Infectious Diseases journal, shows that around 15% of Ebola survivors examined have a retinal scar that appears specific to the disease.

Viruses, like Ebola, can stay hidden in our bodies by exploiting a vulnerability in our immune systems. This vulnerability is called “immune privilege,” and comes from an old observation that foreign tissue transplanted into certain parts of the body don’t elicit the usual immune response. This includes the brain, spinal cord, and eyes. Scientists believe this is because the brain, spinal cord, and eyes are simply too delicate and important to withstand the inflammation that’s typical of an immune response.

An eye team led by Dr Paul Steptoe, compared eye examinations of PES sufferers in Sierra Leone and the control population.

“The distribution of these retinal scars or lesions provides the first observational evidence that the virus enters the eye via the optic nerve to reach the retina in a similar way to West Nile Virus, said Paul Steptoe, part of the research team. “Luckily, they appear to spare the central part of the eye so vision is preserved. Follow up studies are ongoing to assess for any potential recurrence of Ebola eye disease.”

The study also provides preliminary evidence that in survivors with cataracts causing reduced vision but without evident active eye inflammation (uveitis), aqueous fluid analysis does not contain Ebola virus therefore enabling access to cataract surgery for survivors.

This work was supported by The Dowager Countess Eleanor Peel Trust, Bayer Global Ophthalmology Awards Programme, Wellcome Trust ERAES Programme and the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Emerging and Zoonotic Infections at the University of Liverpool.

The full paper, entitled ‘Novel Retinal Lesion in Ebola Survivors, Sierra Leone, 2016’, can be found here https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/23/7/16-1608_article