Francisella tularensis, also called rabbit fever, is an equal opportunity pathogen: it causes the disease tularemia in humans, rabbits and rodents, among others. Despite years of study, the means by which these microbes cause such severe disease remain mysterious.

Tularemia doesn’t seem to spread from person to person. Instead, people contract it from contact with infected animals, from the bite of ticks or deerfly, or from contaminated water or soil. Untreated, tularemia can be lethal; however, it generally responds to antibiotics.

“Francisella tularensis is very pathogenic. Disease can occur even when fewer than 10 bacteria get introduced into the lungs. We don’t study the human pathogenic bacterium in our lab, but use a less pathogenic surrogate called Francisella novicida,” explained Dr. Aria Eshraghi, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Microbiology at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

The low dose required for infectivity and the severity of the disease it causes had led the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to classify F. tularensis as a Category A bioterrorism agent, and to track tularemia cases nationwide, according to Dr. Brook Peterson, a senior scientist at the UW School of Medicine who also participated in the study.

Eshraghi, Peterson and colleagues are among those working to unlock how Francisella tularensis overcomes the body’s defenses, recently published their findings in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

The bacteria have a genome distinguished by a cluster of genes called the Francisella Pathogenicity Island. Some of the genes in this region encode toxins. This region also contains the plans for the machinery that delivers these toxins to animal cells in order to cause disease.

Scientists had thought the Francisella Pathogenicity Island contained all the toxin genes, but the research group then discovered a sort of outside contractor — infection-enhancing proteins not accounted for in the pathogenicity island instructions.

These proteins share features with toxins found in some other pathogens, like the bacterium that causes Legionnaires’ disease. The researchers found evidence that these proteins promote the growth of Francisella within macrophages, white blood cells that usually ingest and digest pathogens.

“Francisella novicida must actively commandeer its host to avoid cellular defenses,” the researchers noted.

The authors said that, until recently, it had been difficult to find new toxins related to tularemia virulence. The reported progress was possible, said project researcher David Veesler, UW assistant professor of biochemistry, because of improved technologies and techniques to capture, describe and catalog bacterial proteins.

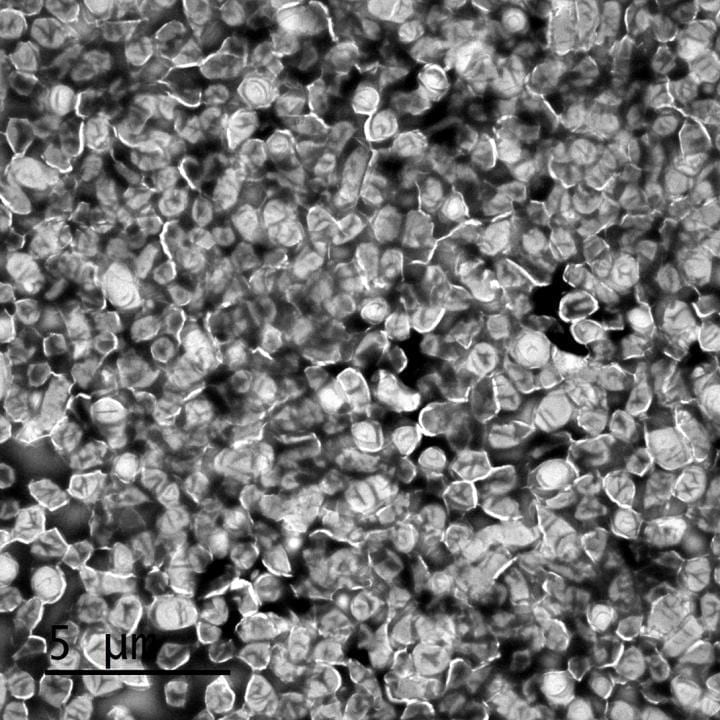

A number of these experimental procedures were performed by their colleagues collaborating on this project. These include more sensitive mass spectrometry for detecting, identifying and quantifying protein molecules, electron microscopy for visualizing an assortment of components of the nano-machine that transports toxins, and fluorescence confocal microscopy, which can label proteins with light emitting dyes.

“We have discovered some of Francisella’s toxins, but still to be determined is how they act on the cells the bacteria infect. That knowledge will be a big advance in our understanding of tularemia,” said senior author Dr. Joseph Mougous, associate professor of microbiology at the UW School of Medicine.

Participating in the project with the UW Medicine microbiologists were researchers in the UW Department of Biochemistry, the University of Maryland, Boston Children’s Hospital and the Paul Allen School for Global Animal Health at Washington State University, which has a researcher, Dr. Jean Celli, with a longstanding interest in tularemia.