The World Health Organization’s (WHO) recently released Global Tuberculosis Report for 2021 paints a dismal picture of the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on the fight against TB across the globe.

Progress against TB has long been inadequate to reach the target of elimination by 2030. But before the pandemic the world was making steady progress in diagnosing and treating TB, and deaths from TB had steadily decreased every year since 2005.

The report is based on annual responses to the WHO from 197 countries. It represents around 99% of the world’s population and TB cases and provides annual feedback to the national and international public health community.

This year it contains very worrying news about the COVID-19 pandemic’s wide-ranging and longer term effects on TB services.

For the first time since 2005, the number of deaths due to TB increased from one year to the next. In 2020 there were 1.3 million deaths among HIV-negative people and 214,000 among HIV-positive people. In 2019 the death numbers were 1.2 million among HIV-negative and 209,000 among HIV-positive people.

Mathematical modelling projections for the 16 worst affected countries, including South Africa, suggest the knock-on effect will be worse in 2021 and beyond. These countries are likely to suffer even greater increases in the number of new cases and deaths from TB.

The most urgent priority, according to the report, is to restore access to and provision of TB services to enable levels of TB case detection and treatment to recover to pre-pandemic levels. In the longer term, countries must invest in research and innovation to address the priority needs. These are: TB vaccines to reduce the risk of infection and the risk of disease in those already infected; rapid diagnostics for use at the point of care; and simpler, shorter treatments for TB disease.

Why Gains in TB Control Have Been Reversed

COVID-19 has had a large negative effect on all health services. The effect on TB services has been profound. This is especially the case with regard to TB diagnosis – the essential first step to treating TB and preventing death.

The number of people newly diagnosed with TB had increased annually between 2017 and 2019. But there was a startling drop of nearly 20% between 2019 and 2020 from 7.1 million to 5.8 million. In contrast, the number of TB deaths increased by about 10%, taking us back to 2017 levels.

In the 2021 report, 16 countries accounted for 93% of the total global drop in new TB diagnoses of 1.3 million. The worst affected were India, Indonesia and the Philippines. These three countries are among a group of 10, including South Africa, considered high-burden countries for drug sensitive, drug resistant and HIV-associated TB.

The new data shows that the gap between reality and targets in high burden countries has widened dramatically.

The COVID-19 epidemic has had many consequences for TB services.

The report notes these three:

- patients have delayed seeking care due to restrictions on movement,

- reduced likelihood of diagnosis because of resource constraints,

- reduced treatment initiation because of medicine supply interruptions and stockouts.

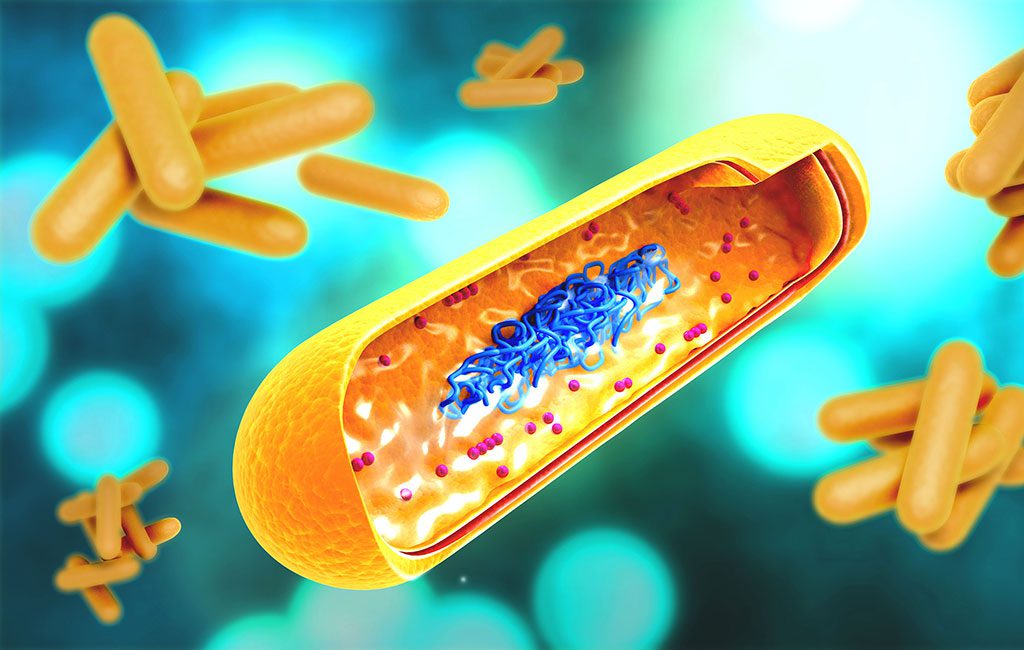

Model estimates of future impact may also be underestimates, as they do not account for the negative effects of COVID-19 on the social determinants of TB. For example, low income and malnutrition increase the chances of developing TB disease in people who are already infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the infectious agent that causes TB disease.

Trend Will Continue Unless the World Acts Now

The increased number of undiagnosed and untreated TB cases will lead to more TB transmission and a further increase in TB disease and death in the years to come unless action is taken now.

TB preventive treatment is given to people who are at high risk of developing TB disease after being infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The WHO recommends that TB preventive therapy be given to people living with HIV, household contacts of individuals diagnosed with TB of the lungs, and certain people with co-morbidities such as those receiving dialysis or diabetics.

Unfortunately, services for TB preventive treatment have also suffered setbacks in the past 18 months. Globally the number of people who received TB preventive treatment had increased by over 250% from 2015 to 2019. But this trend reversed in 2020 with a 21% reduction from 3.6 million to 2.8 million. Substantial action and resources must be directed towards the provision of TB prevention treatment to people who meet the criteria.

The standard of care for drug sensitive TB disease is a six-month course of treatment. On a positive note, the report shows that more countries (36, up from 21) are using newly recommended, shorter treatment regimens for drug susceptible TB.

TB is a leading cause of death in people with HIV. The absolute number of people diagnosed with TB who knew their HIV status fell by 15% in 2020. But the global coverage of HIV testing among people diagnosed with TB remained high in 2020. Treating TB and providing ARVs to HIV-positive people diagnosed with TB is estimated to have averted 66 million deaths between 2000 and 2020.

Catching Up

The first South African National Prevalence survey and other emerging research has shown that only about half of people with active TB disease report having one of the classic symptoms of TB disease: cough, fever, weight loss and night sweats.

This implies that people in the early stages of active TB disease, without any recognisable symptoms, may be contributing to TB transmission without knowing it. It is vitally important that attempts to recover from COVID-19 setbacks, such as catch-up campaigns for case-finding and treatment, involve methods to find people with TB who do not have symptoms as well as those who do.

It is sobering to reflect that, during the 18 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, about 90,500 South Africans have died of TB – more than the 88,754 reported to have died of COVID-19 during the same period. The COVID pandemic has proved that health systems are capable of making drastic changes when the need arises. It is time to apply the same determination to fighting TB.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Indira Govender, Research fellow, clinical research at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Africa Health Research Institute (AHRI). Dr. Govender is a medical doctor and public health medicine specialist, based at the Africa Health Research Institute in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Indira has been working in rural health services since 2013. At AHRI, Indira works on population-based research projects related to TB infection prevention and control and understanding TB infectiousness. Her advocacy interests are rural health, primary health care, access to care, sexual and reproductive justice and anti-racism.

Alison Grant, Professor of International Health at LSHTM and Member of Faculty, Africa Health Research Institute (AHRI). Dr. Grant is member of Faculty at Africa Health Research Institute (AHRI) and a Professor of International Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). She initially trained as a physician specialising in infectious and tropical diseases and HIV medicine, and continues to see patients at the Mortimer Market centre HIV clinic in London. Prof Grant also holds a PhD in epidemiology. Her main research interest is improving care for HIV-positive people in resource-limited settings, and preventing tuberculosis (TB). Since 1997, Prof Grant’s research has primarily been based in South Africa where her work has focussed on the development and evaluation of interventions to reduce HIV-related illness and death, and particularly HIV-related TB. Major projects she has led and collaborated on include a programme of work taking a whole systems approach to TB infection prevention and control in primary healthcare clinics; a study investigating TB transmission from people with subclinical TB; and a cluster-randomised trial investigating a point-of-care TB test and treat algorithm for people with advanced HIV disease.

Al Leslie, Faculty Member, Africa Health Research Institute; Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow, UCL. Dr. Leslie’s work is devoted to understanding the relationship between HIV and its host, focussing on immune cells’ earliest response to the pathogen. Recently, he’s expanded those studies to include the tuberculosis-causing bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Al initially trained in agricultural science. He went on to do a PhD in HIV Immunology at Oxford University after witnessing first-hand the devastation wrought by HIV in the late 1990s while he was working in Malawi. Al took up a position as an Investigator at the KwaZulu-Natal Research Institute for TB-HIV in 2012. He is a member of AHRI Faculty, where his lab works to understand how human cells respond to infection with HIV and tuberculosis.

Emily B. Wong, Assistant Professor, Africa Health Research Institute (AHRI). Dr. Wong is a physician-scientist whose work focuses on trying to understand the impact of HIV infection on TB pathogenesis, immunity and epidemiology. To address these questions she uses a range of techniques that span molecular to population science. She is a member of the resident faculty of the Africa Health Research Institute (AHRI) in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa and an Assistant Professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. Emily specializes in establishing unique human cohorts to address fundamental questions about human infectious disease and immune responses.

Yumna Moosa, Africa Health Research Institute (AHRI). Dr. Moosa holds a MBChB degree from the University of Cape Town, and a master’s degree in virology and bioinformatics from UKZN. She is a vocal advocate for fair working conditions for junior healthcare workers. She studied pure mathematics during her medical internship, and completed her part-time Masters degree during her community service, pregnancy and first year of parenthood. In order to integrate her various skills and experiences she has embarked on a PhD programme to harness advanced computational techniques to address questions that affect the health of vulnerable people. Her current research at AHRI involves integrating clinical, genomic and spatial data to understand tuberculosis transmission. She also has a special interest in gender-based violence and women’s health.

This article is courtesy of The Conversation.