The South Dakota Department of Health has confirmed the first human case of West Nile virus (WNV) in 2025—a Brookings County resident—marking the official start of a mosquito season that could have wide-ranging public health implications. Since its first appearance in the state in 2002, WNV has caused more than 2,864 human cases and 54 deaths in South Dakota alone. The state remains one of the nation’s epicenters for neuroinvasive forms of the disease, raising concern as the summer mosquito season intensifies.

“The rate of severe infection that includes swelling of the brain and spinal cord… is highest in South Dakota and other Midwest states,” noted Dr. Joshua Clayton, the state’s epidemiologist. “Raising awareness of human cases can ensure residents and visitors alike take action to reduce their risk.”

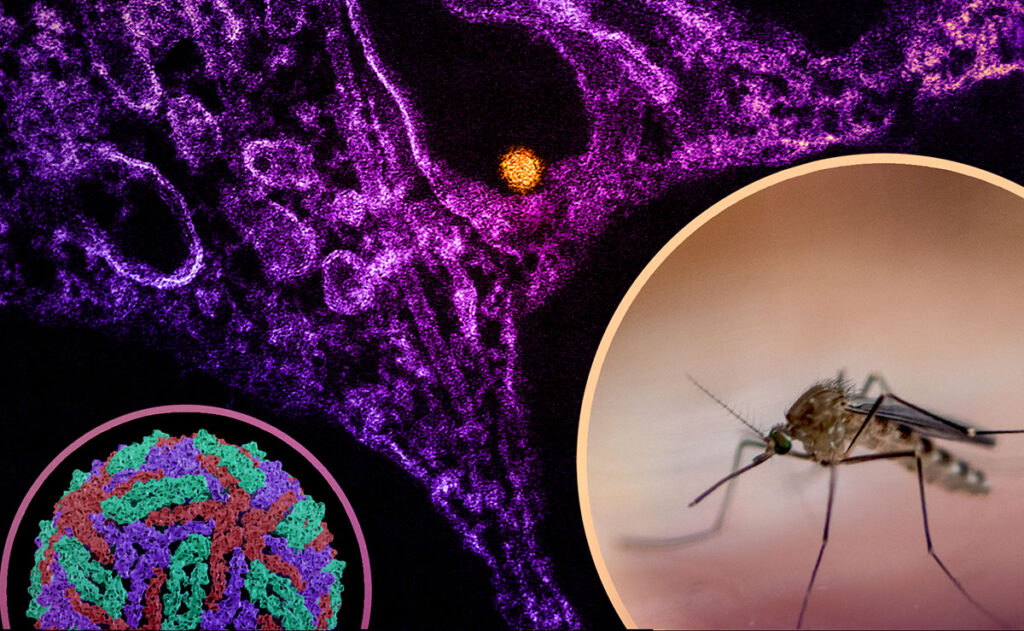

West Nile virus, a mosquito-borne flavivirus, is primarily transmitted by Culex tarsalis mosquitoes in South Dakota. While most human infections are asymptomatic or result in mild febrile illness, about 1 in 150 cases progress to neuroinvasive disease, which can cause encephalitis, meningitis, or acute flaccid paralysis.

A Rare and Alarming Case: WNV and Poliomyelitis Syndrome

Just weeks before South Dakota’s first 2025 case was reported, a publication in SAGE Open Medical Case Reports documented a harrowing fatal case of WNV-associated poliomyelitis syndrome in an 83-year-old Alabama resident. The case, which progressed rapidly from flu-like symptoms to quadriplegia, bulbar palsy, and respiratory failure, is a stark reminder of how quickly WNV can cause devastating neurologic outcomes in older or immunocompromised individuals.

Despite prompt diagnosis and a full course of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), the patient succumbed to the disease. This underscores the lack of definitive therapies for WNV and highlights the urgent need for randomized trials to evaluate treatments such as IVIG and plasma exchange.

The Broader Threat: Vector-Borne Disease and Health Security

Vector-borne diseases like West Nile virus are becoming more complex amid climate-driven shifts in mosquito distribution and behavior. Warmer temperatures and altered precipitation patterns are contributing to longer transmission seasons and expanded geographic ranges for mosquito species, increasing the potential for WNV and similar pathogens to spread into new areas and populations.

For public health and clinical communities, this presents a multi-faceted challenge:

- Clinician awareness: Timely diagnosis is critical but often hindered by non-specific early symptoms. Health professionals must maintain a high index of suspicion for arboviral illnesses, especially during mosquito season.

- Surveillance and vector control: Early case detection and mosquito population monitoring remain cornerstones of prevention, particularly in regions with endemic transmission.

- Community prevention: Personal protection against mosquito bites—through repellents, clothing, and reducing standing water—is still the most effective public health measure.

Implications for the General Public and National Interest

Though severe cases of WNV are rare, their consequences can be catastrophic. The elderly and individuals with chronic health conditions are especially vulnerable to neuroinvasive disease, making public awareness and prevention strategies vital for community health. At the national level, recurrent and expanding outbreaks of WNV strain local healthcare infrastructure, reduce workforce productivity, and expose gaps in preparedness for vector-borne disease threats.

WNV also exemplifies how infectious disease risk is not confined to exotic pathogens abroad but persists in endemic form here in the United States. With no licensed human vaccine or antiviral treatment currently available, safeguarding public health requires proactive investments in mosquito control, research and development of therapeutics, and robust public health communication strategies.

Practical Steps for Individuals and Communities

The South Dakota Department of Health recommends the following to reduce WNV risk:

- Apply mosquito repellent with EPA-approved ingredients such as DEET, picaridin, oil of lemon eucalyptus, or IR3535.

- Wear protective clothing—long sleeves and pants—especially from dusk to midnight when mosquitoes are most active.

- Eliminate standing water in birdbaths, pet dishes, flowerpots, and other outdoor containers.

- Support local mosquito control programs and remain informed via state and local public health websites.

These precautions are particularly crucial for high-risk groups, including people over 50, transplant recipients, pregnant women, and those with underlying health conditions.

As West Nile virus season unfolds across the Midwest, the first confirmed case in South Dakota should serve as both a local alert and a national call to action. In an era of accelerating vector-borne disease threats, vigilance, prevention, and preparedness are essential tools in protecting individual health and securing national biosecurity.

Sources and Further Reading

- South Dakota Department of Health. First Human West Nile Virus Case of 2025 Reported in Brookings County. Read the full press release

- Easow B, Qureshi M, Mandyam S, et al. West Nile neuroinvasive disease with poliomyelitis syndrome: A grave phenomenon. SAGE Open Medical Case Reports, 24 June 2025. Read the case report summary

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). West Nile Virus Information

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not intended to provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Readers should consult a qualified healthcare professional for medical concerns. For more information on vector-borne disease surveillance, prevention tools, and treatment research, consult local and federal public health authorities.