The global spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1—particularly the GsGd lineage clade 2.3.4.4b—has reached unprecedented levels in birds, livestock, wildlife, and even a small number of humans. New data compiled in August 2025 by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security Science & Technology Directorate (DHS S&T) highlights a series of critical developments in the ongoing outbreak, including spillover into domestic ruminants such as dairy cattle and goats, and limited human infections tied to animal exposure.

While human-to-human transmission has not been observed, the scale of the outbreak and its expanding host range underscore an urgent need for sustained biosurveillance, cross-sector preparedness, and public awareness.

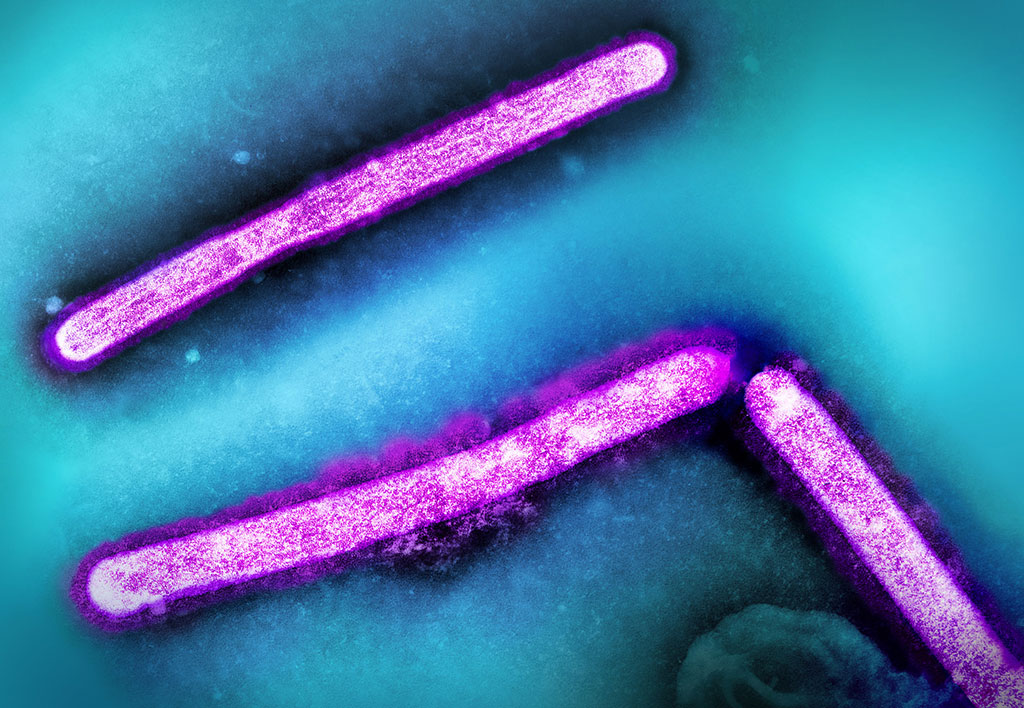

A Virus That Crosses Species Barriers

Since February 2022, the HPAI H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b outbreak has swept through wild and domestic birds on nearly every continent—including recently Antarctica—and expanded into mammals at a rate not previously documented for avian influenza.

As of June 2025, the United States has seen:

- 174.8 million birds affected across all 50 states and one territory.

- 1,703 livestock herds in 18 states testing positive for HPAI, with Texas, Idaho, Colorado, Michigan, and Ohio reporting the highest numbers.

- 41 human cases linked to infected dairy cattle and 24 linked to poultry, plus several others of unknown or alternative animal exposure. One U.S. death has been recorded—an older adult with underlying conditions.

Internationally, human HPAI cases have been confirmed in countries including Mexico, Cambodia, the United Kingdom, and Australia. The virus’s ability to reassort genetically—as seen historically with the 1918 Spanish flu and the 2009 H1N1 pandemic—remains a key concern for global health security.

Persistent Environmental Risks and Transmission Pathways

HPAI viruses can remain infectious on smooth, nonporous surfaces for up to two weeks under cool conditions, and can persist in cold fresh water for several weeks to months depending on temperature and sunlight exposure. This increases the risk of indirect transmission between farms or through contaminated equipment. Dairy cattle are most susceptible via the mammary route, which explains the virus’s detection in milk and milking equipment. Migratory waterfowl continue to play a pivotal role in disseminating new virus strains along their flyways.

To date, there is no evidence of sustained human-to-human spread. Most human infections arise from direct contact with infected birds, livestock, or contaminated environments. Pasteurized dairy products and properly cooked poultry remain safe for consumption according to USDA and FDA risk assessments.

Surveillance, Biosecurity, and Countermeasures

The United States has implemented the National Milk Testing Strategy to screen herds and monitor the milk supply chain. Standard rRT-PCR testing, enhanced farm-level biosecurity, and personal protective equipment (N95-equivalent respirators, gloves, fluid-resistant coveralls) are central to containment efforts.

For animals, depopulation of infected poultry flocks remains the primary control measure, while palliative care—not culling—is advised for infected cattle.

For humans with confirmed or suspected infection, neuraminidase-inhibitor antivirals such as oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir remain effective if administered early. Seasonal flu vaccines do not protect against H5N1, though several poultry vaccines and a limited stockpile of human H5N1 vaccines exist for emergency use.

Additional Technical Highlights

Incubation Period:

- In birds: Typically 1–5 days after exposure, shorter in highly susceptible domestic poultry.

- In mammals: Usually 2–7 days; for human H5N1 infections, onset most often occurs within 3–5 days post-exposure.

- Incubation can be longer (up to 10days) in rare cases following lower-dose exposures or in cooler conditions.

Clinical Presentation:

- Humans: Often begins with fever, cough, sore throat, and conjunctivitis, sometimes followed by rapidly progressive viral pneumonia and respiratory distress; gastrointestinal symptoms are more frequent than in seasonal influenza.

- Cattle: Most prominent sign is sharp reduction in milk yield with thickened or clotted milk; affected animals may appear otherwise clinically normal.

- Wild and domestic birds: Severe neurologic signs (e.g., ataxia, tremors) and high mortality, particularly in gallinaceous poultry (domesticated land-fowl such as chickens, turkeys, quail, and pheasants).

Biosurveillance Advances:

- DHS S&T highlights the importance of integrated One Health surveillance linking wild bird die-off data, livestock testing, and wastewater surveillance for early warning of viral spread.

- Emphasis on genomic sequencing of circulating H5N1 strains to track adaptive mutations such as PB2-E627K and HA cleavage-site changes that may alter host range or virulence.

- Migratory waterfowl flyway mapping remains central to predicting seasonal incursions into domestic poultry regions.

Clinical Diagnostics

- Real-time RT-PCR (rRT-PCR) is the primary confirmatory test for avian and mammalian cases; the MQL notes nasopharyngeal swabs and lower respiratory samples provide highest sensitivity in humans.

- Milk and raw-dairy sample testing for viral RNA has been incorporated into USDA’s National Milk Testing Strategy; positive milk typically shows low cycle threshold (Ct) values, reflecting substantial viral load.

- Virus isolation in embryonated chicken eggs remains the reference standard for characterization but is slower and requires BSL-3 containment.

Countermeasure Insights:

- Antivirals: Early treatment with neuraminidase inhibitors (oseltamivir, zanamivir, peramivir) continues to show benefit; resistance monitoring is advised in ongoing outbreaks.

- Vaccines: A limited H5N1 vaccine stockpile for humans exists under federal preparedness programs; several inactivated and vector-based poultry vaccines are available but not yet deployed at national scale.

- PPE guidance: Reiterates the importance of N95-equivalent respirators, fluid-resistant coveralls, gloves, and eye protection for those handling infected animals or high-risk specimens.

Why This Matters for Public Health Security and National Interest

Beyond its immediate impact on animal health and agricultural productivity, the HPAI outbreak exemplifies the growing intersection of zoonotic disease, food security, and economic resilience. Unchecked, such cross-species influenza events can disrupt livestock supply chains, affect trade, and pose spillover threats to human populations.

Robust early detection and coordinated multi-agency response—spanning USDA, CDC, FDA, DHS, and international partners—are therefore critical components of national security and global health preparedness.

Key Takeaways for Professionals

- Expanded Host Range: HPAI is no longer confined to poultry; recent infections in cattle, goats, cats, and wildlife underscore the need for One Health surveillance.

- Continued Evolution: Genetic reassortment could give rise to more human-adapted strains; genomic monitoring for mutations such as PB2 E627K is vital.

- Environmental Stability: The virus’s persistence on surfaces and in water highlights the importance of rigorous disinfection protocols on farms and in processing facilities.

- Risk Communication: Transparent messaging to farmers, veterinarians, clinicians, and the general public helps curb misinformation and supports rapid reporting of suspect cases.

Looking Ahead

The DHS S&T report makes clear that despite the absence of sustained human-to-human transmission, HPAI remains a pandemic-capable virus family. Preventing the next influenza pandemic depends on collaborative global surveillance, continued research into effective livestock vaccines, and preparedness planning for potential shifts in the virus’s transmissibility.