The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has entered a critical phase in its management of Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) with a new outbreak in Kasai Province. Declared by the Ministry of Health on Sept. 4, 2025, this outbreak—the country’s sixteenth since 1976—arises in a context of systemic fragility: protracted humanitarian crises, resource-limited health infrastructure, and concurrent epidemics of mpox, cholera, and measles.

Recognising the potential for rapid escalation and cross-border transmission, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) classified the event as a Red Emergency and launched a $18 million USD Emergency Appeal on Sept. 16 to scale up response operations. The outbreak’s epicentre is in Bulape and Mweka health zones, an area of approximately 3.5 million people, where health facilities are sparse and road networks remain severely degraded.

Epidemiological Situation

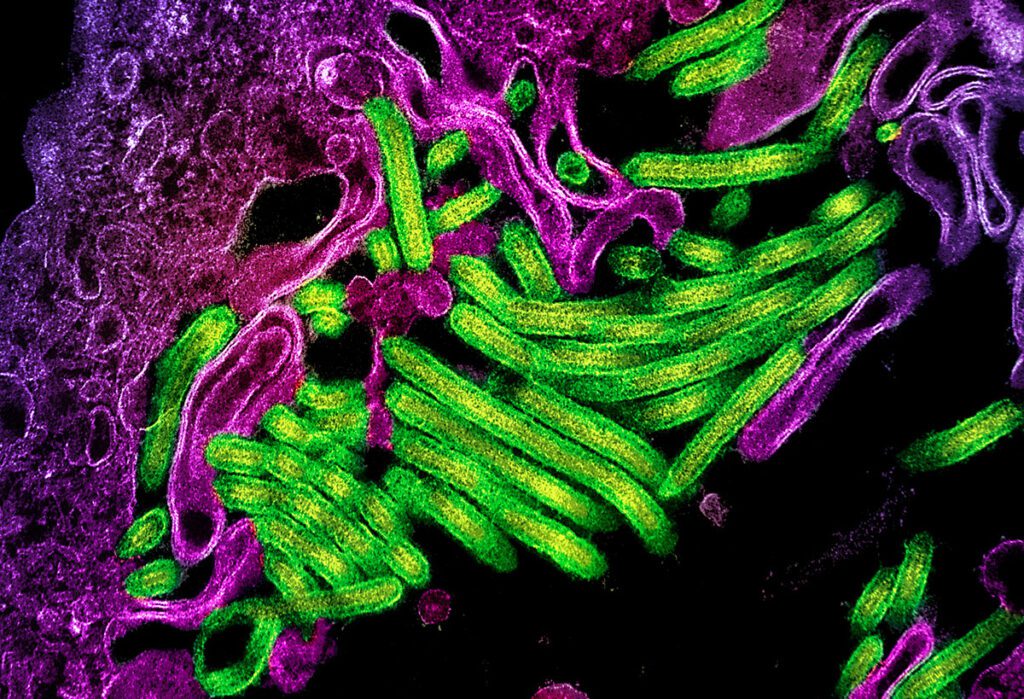

Laboratory confirmation of Orthoebolavirus zairense from three initial samples collected in Bulape signalled the outbreak’s onset. As of Sept. 28, 2025, there are 64 people with confirmed or probable Ebola, which includes 42 deaths, a case-fatality rate (CFR) approaching 66%. At least five healthcare workers were infected, underscoring gaps in infection prevention and control (IPC).

The index case—a 34-year-old pregnant woman—presented with acute haemorrhagic syndrome on August 20 and succumbed within five days, highlighting delays in case recognition and limited early diagnostic capacity. Geographic risk mapping shows significant vulnerability for inter-provincial and cross-border dissemination, as Kasai shares borders with seven provinces and Angola. Travel corridors—particularly the Tshikapa-Kinshasa route—pose potential pathways for seeding new transmission foci if response measures falter.

Operational and Logistical Challenges

The outbreak response unfolds amid high baseline vulnerability: over 40% of children under five in Kasai are stunted, with >2,000 currently under treatment for acute malnutrition. These conditions heighten morbidity and mortality risks and may exacerbate health-seeking delays.

Severe logistical bottlenecks continue to impede containment: travel between Bulape and Mweka—only 27 km (~17 miles) apart—can take around 12 hours due to poor road infrastructure. Such delays affect the timely delivery of PPE, diagnostic supplies, and deployment of rapid response teams. Concurrent seasonal flooding further threatens access to high-risk communities.

Educational disruption has affected >44,000 school-aged children in the affected zones. Psychosocial stress and stigma remain significant, echoing patterns seen in prior outbreaks and increasing the burden on frontline health workers.

Response Architecture

The IFRC, in collaboration with the DRC Ministry of Health, WHO (graded the outbreak a Level 3 emergency on September 5), UNICEF, MSF, and other humanitarian actors, has activated an integrated containment strategy.

Surveillance & Contact Tracing: Retrospective case finding back to July, expanded contact identification in Bulape and adjacent health zones, and targeted screening at points of entry.

Vaccination: Ring vaccination of frontline healthcare workers, primary contacts, and secondary contacts began Sept. 13 using the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (Ervebo) vaccine; 2,000 pre-positioned doses were deployed from Kinshasa, with an additional 43,840 doses allocated to extend coverage.

Safe and Dignified Burials (SDBs): Expansion from two to ten operational SDB teams to reduce community-linked transmission.

Infection Prevention & Control (IPC) / WASH: Scale-up of decontamination of households and public spaces, installation of hand-hygiene stations, and provision of safe water to treatment centres and vulnerable communities.

Risk Communication & Community Engagement (RCCE): Local community committees—adapted from successful models in Beni during the 10th outbreak—are being leveraged to address misinformation and resistance to SDBs and isolation.

Mental Health & Psychosocial Support (MHPSS): Rapid deployment of psychological first aid for patients, survivors, and staff.

Protection, Gender & Inclusion (PGI): Enhanced attention to gender-based violence risks and accessibility of services for vulnerable groups.

The IFRC Emergency Appeal targets 965,000 beneficiaries, encompassing exposed populations, healthcare workers, and at-risk border communities.

Health Security and National Interest

Although geographically localized, the Kasai outbreak has strategic implications for national and regional health security. A recent Lancet analysis warns that road-limited access does not eliminate cross-border risk—especially given links between Kasai, Tshikapa, Kinshasa, and Angola’s northern provinces.

Rapid containment protects critical health services, economic activity, and social stability, while preserving regional trade and travel corridors. For the general population, effective outbreak control translates to sustained healthcare access, preserved livelihoods, and reduced risk of conflict-driven destabilization. Strengthened surveillance, laboratory capacity, and WASH infrastructure serve as dual-use investments, enhancing preparedness for other high-consequence pathogens.

Forward-Looking Considerations

This outbreak reinforces several technical imperatives for future epidemic preparedness in the DRC and similar contexts:

- Timely case investigation and early diagnostic surge capacity to narrow the delay between symptom onset and isolation.

- Sustained IPC capacity-building at primary care level, especially for obstetric units.

- Integrated data and modelling teams to optimize resource allocation and assess real-time transmission dynamics.

- Robust cross-border surveillance protocols and harmonized reporting to prevent regional seeding events.

- Continued community-centered strategies to mitigate resistance and promote adherence to evidence-based containment.

The Kasai response demonstrates that technical rigor, cross-sector coordination, and locally-led engagement remain central pillars of successful outbreak containment in resource-limited, high-risk settings.

Sources and Further Reading:

IFRC: Ebola DRC Emergency Appeal

The Lancet: New Ebola virus disease outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: early response guidance

JHU Center for Outbreak Response Innovation: Factsheet on Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Nature: Ebola outbreak in the DRC: why is it so deadly?

Africa CDC: New Ebola outbreak confirmed in the Democratic Republic of Congo