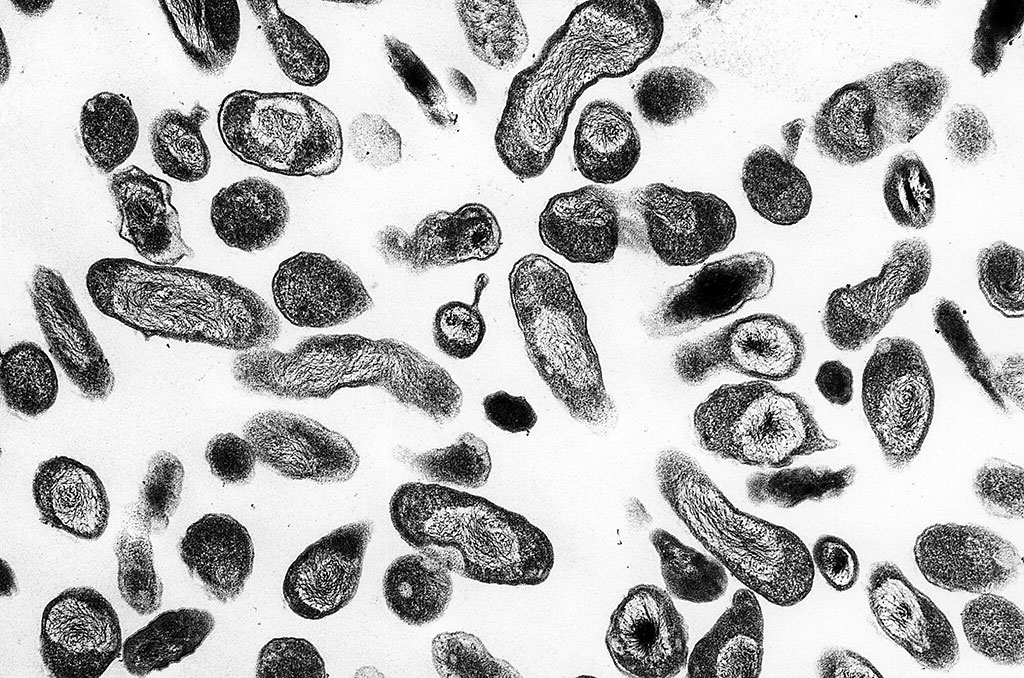

Persistent fever is one of the most challenging syndromes to evaluate in low-resource settings, where malaria, leishmaniasis, and other tropical diseases dominate the diagnostic landscape. But new research published in Microbiology Spectrum indicates that Coxiella burnetii—the bacterium that causes Q fever—may be complicating this picture.

The pathogen, which is also classified by U.S. federal authorities as a Select Agent because of its biothreat potential, was found alongside Bartonella species in patients who already had confirmed infectious or inflammatory causes of fever.

The study analyzed biobanked serum samples from more than 1,300 patients in Sudan, Nepal, and Cambodia who were enrolled in the multi-country NIDIAG fever cohort. Using immunofluorescence antibody assays, the researchers examined whether these culture-negative bacteria could be detected in patients whose persistent fevers had already been attributed to another diagnosis.

Unexpected Seropositivity

Among the 1,313 individuals tested, 4.3% were seropositive for C. burnetii and 4.6% for Bartonella species. Notably, 44 patients (3.4%) were positive for both pathogens, suggesting either cross-reactivity of the assays or the possibility of overlapping exposures and co-infections.

- C. burnetii positivity was relatively consistent across the three study countries, with rates of 5.2% in Sudan, 3.7% in Nepal, and 3.7% in Cambodia.

- Bartonella seropositivity varied more widely: 11.3% in Nepal compared with only 1.6% in Sudan and 0.6% in Cambodia.

Links with Other Diagnoses

When compared to a reference group of patients with common bacterial infections, C. burnetii and Bartonella positivity appeared more frequently in individuals with specific diseases:

- Visceral leishmaniasis, P. falciparum malaria, leptospirosis, brucellosis, scrub typhus, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) all showed higher rates of seropositivity.

- The strongest associations were observed for scrub typhus (Bartonella seropositivity in 63.6% of cases) and SLE (42.9% positive for C. burnetii and 28.7% for Bartonella).

These findings suggest that background seropositivity or cross-reactivity could confound interpretation in settings where such diseases are endemic.

Diagnostic Crossroads in Low-Resource Settings

Both C. burnetii and Bartonella are fastidious organisms not detectable with standard culture techniques, making serology a cornerstone of diagnosis. Yet serologic cross-reactivity is well documented, both between these pathogens and with others such as Rickettsia, Legionella, and Brucella.

This study underscores how reliance on serology in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) can blur the distinction between true infection, prior exposure, and false positives. Misdiagnosis risks are significant: for example, patients with positive serology might be labeled with Q fever or bartonellosis when their fevers are actually due to malaria or leishmaniasis, or vice versa.

Implications for Global Health Security

The detection of C. burnetii is particularly notable because of its dual identity: both as a naturally circulating zoonosis and as a federally regulated Select Agent in the United States. Its ability to cause outbreaks through aerosol transmission and its persistence in animal reservoirs make it a pathogen of concern for public health surveillance, veterinary medicine, and biodefense.

For global health stakeholders, the findings highlight the urgent need for improved diagnostic tools—particularly molecular assays or confirmatory tests—that can distinguish true infection from cross-reactivity in LMIC contexts.

Challenges Ahead

The authors acknowledge limitations, including small sample sizes for certain diseases, lack of paired acute-convalescent sera, and the inability to deploy confirmatory methods such as cross-adsorption or molecular testing. These gaps leave unanswered whether the serologic signals reflect genuine co-infection, previous exposure, or assay limitations.

Nonetheless, the study provides a rare window into the diagnostic complexity of persistent fever in resource-limited settings. It highlights the need for context-specific validation of serologic assays and reinforces the broader point that pathogens like C. burnetii and Bartonella may be hidden contributors—or confounders—in the already crowded landscape of tropical febrile illness.

Boodman C, Edouard S, van Griensven J, et al. Coxiella burnetii and Bartonella species serology of febrile patients with an established infectious or inflammatory diagnosis in Sudan, Nepal, and Cambodia. Microbiology Spectrum. 19 September 2025.

The study was conducted by a consortium of researchers from multiple international institutions, including:

- Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Manitoba (Canada)

- Institute of Tropical Medicine (ITM), Antwerp (Belgium)

- Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire en Maladies Infectieuses (IHU–Méditerranée Infection), Marseille (France), which also houses the French Reference Center for rickettsioses, Q fever, and bartonelloses

- B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences (Dharan, Nepal)

- Faculty of Medicine, University of Khartoum (Sudan)

- Sihanouk Hospital Center of HOPE (Phnom Penh, Cambodia)

- Institut National de Recherche Biomédicale (INRB) (Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo)

- Geneva University Hospitals (HUG), Division of Tropical and Humanitarian Medicine (Switzerland)

- McGill University Health Centre and the JD MacLean Centre for Tropical and Geographic Medicine (Montreal, Canada)

- Kasturba Medical College, Manipal Academy of Higher Education (India)