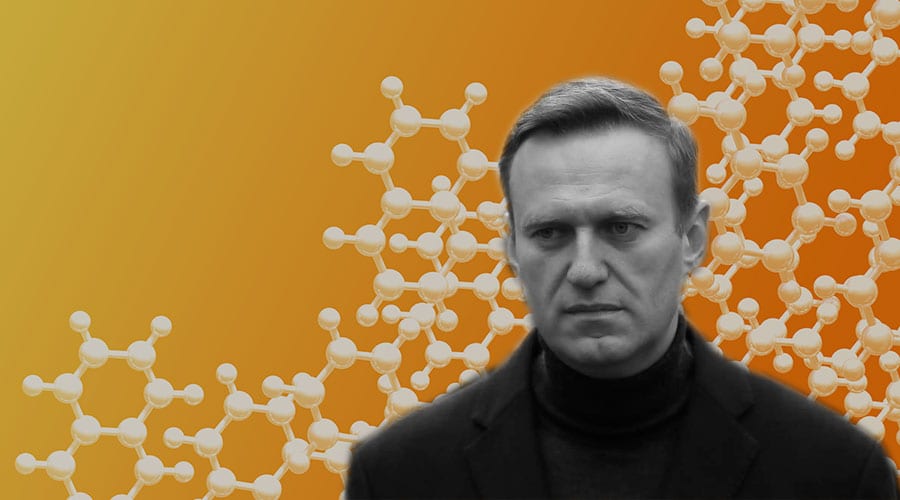

Germany’s announcement on September 2 that the chemical used to poison Alexei Navalny, the most prominent opposition figure in Russia today, was a member of the Novichok family of nerve agents confirms what most observers suspected all along: that the Russian government was responsible for the sudden illness that overtook Navalny while he was traveling from Siberia to Moscow on August 20th. The poisoning of Navalny, who is currently recovering in a German hospital, is only the latest addition to the tragically long list of dissidents and critics, in both Russia and abroad, who have been poisoned by the Kremlin. While the use of a Novichok agent would appear to draw unwanted attention to the poisoning of Putin’s most high-profile critic, that was most likely the point. Putin, who most likely views the recent unprecedented mass protests against President Aleksandr Lukashenko in neighboring Belarus with a great deal of trepidation, is exploiting the special dread associated with poison and capitalizing on the implausible deniability associated with the use of a Novichok agent to send a clear signal to the political opposition in Russia: defy me and you will die. This approach bears an eerie similarity to the strategy that Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has perfected over the course of that country’s civil war. Putin, like Assad, views chemical weapons as a useful means of repression in service of regime security and brazenly violates the international treaty that bans these weapons as a means of intimidating the opposition to his regime.

From Russia With Poison

No other chemical weapon is as closely associated with Russia as the family of nerve agents known colloquially as Novichok, which means newcomer in Russian. This class of nerve agents was developed by the Soviet Union in the 1970s as part of a program codenamed Foliant to modernize the Soviet Union’s chemical weapons arsenal. Some Novichok agents are reportedly five to eight times more lethal than the nerve agent VX, the deadliest chemical warfare agent developed by the United States, and the Soviet military prized their ability to avoid NATO-issued chemical detectors and arms control verification measures being developed at the time. A Soviet-era chemical weapons scientist turned whistleblower, Vil Mirzayanov, publicized the existence of this new class of chemical weapons in the 1990s, but his warnings were largely ignored.

Novichok agents first gained public attention in March 2018 when they were implicated in the attempted assassination of a former Russian spy, Sergei Skripal, in the United Kingdom. That poisoning, which also affected Skripal’s daughter, two police officers, and two British civilians, one of whom died, triggered a sharp but limited response from the United Kingdom and its allies. Approximately 140 Russian “diplomats” were expelled from 27 countries, the European Union imposed sanctions on high-ranking members of the GRU, the Russian military intelligence agency responsible for the attempted assassination, and the United States imposed a handful of economic sanctions on Russia.

In November 2019, in a triumph of international diplomacy, the members of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), the international organization charged with implementing the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) which bans chemical weapons, agreed unanimously to add a number of Novichok agents to the list of chemical warfare agents whose possession is banned and are subject to strict verification measures. Russia was an active participant in the negotiations leading up to this first-ever modification of the list of chemicals covered by the CWC. For Russia to again resort to the use of a Novichok agent for the purpose of assassination is a clear sign that not only does the Kremlin not care about upholding its commitments under CWC, but that it derives a special satisfaction in violating them. In this, Putin borrowed a page from Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s playbook for how to use chemical weapons to weaken the opposition and strengthen regime security.

Red Lines, Regime Security, and Chemical Weapons in Syria

In August 2013, the Syrian dictator defied President Barack Obama’s “red line” and used rockets filled with the nerve agent sarin to kill more than 1,000 men, women, and children in the Damascus suburb of East Ghouta. Under threat from American military action, Assad agreed to give up his chemical weapons and join the CWC. But in April 2014 Syria resumed using chemical weapons: this time dropping barrel bombs filled with chlorine onto rebel-held towns. Although nowhere near as deadly as sarin, these chlorine barrel bombs were sufficiently deadly to terrorize civilians. Even worse, these attacks occurred while Syria was in the process of destroying the stockpile of chemical weapon precursors it had declared to the OPCW in 2013.

Not only did Assad use one type of chemical weapon while pretending to get rid of another type, he got away with it. Despite multiple investigations by the OPCW and the UN Security Council that repeatedly confirmed Syria’s use of chemical weapons, Russia was able to shield Syria from international sanctions. Not until Assad used a sarin-filled bomb on the town of Khan Sheikhoun in April 2017, which killed roughly 100 civilians, did Syria suffer any direct consequences, in the form of a U.S. cruise missile strike on the airbase from which the chemical attack had been launched. Even this was insufficient to deter the Assad regime from continuing to use chemical weapons against rebel-held areas, including the Damascus suburb of Ghouta once again. Following a chlorine barrel bomb attack on Ghouta on April 7, 2018 that killed more than 40 people, a joint American-French-British missile strike destroyed Syria’s major chemical weapon research and development facility in Damascus and hidden caches of precursor chemicals and production equipment.

Assad’s use of chemical weapons throughout the civil war, from crude barrel bombs filled with chlorine to sophisticated binary chemical bombs filled with sarin, puzzled some observers. Why would Assad use these weapons so blatantly, especially after agreeing to get rid of them and knowing the eyes of the world were upon him? From a strictly military perspective, most of these chemical attacks were failures as they did not inflict many casualties, did not change the outcome of the conflict on the ground, and ran the risk of provoking a major military intervention by the United States and its allies. This calculus misses the point: Syria’s chemical weapons were primarily terror weapons, not military weapons. While Western nations view chemical weapons as weapons of mass destruction whose primary purpose is to deter threats to national security and are used primarily on the battlefield, authoritarian leaders like Assad view these weapons as tools to ensure the security of his regime. As a result, the Assad regime’s use of chemical weapons has been dictated primarily by the ebb and flow of the civil war and not by pronouncements from the White House or the UN Security Council. When Assad feels that his “red lines,” such as the security of Damascus and Latakia province, are threatened, he has deployed chemical weapons as a gruesome form of signaling aimed at the opposition. Indeed, Syria’s large-scale uses of sarin have occurred only when Damascus is under threat: such as during rebel offensives against the capital in August 2013 and March-April 2017. Likewise, Syria resumed using chemical weapons in April 2014, despite its promise to get rid of these weapons, when rebels invaded Latakia province, the heartland of the Alawite ethnic group that provides the foundation for Assad’s hold on power.

While the Assad regime consistently denies that is uses chemical weapons, it has not hidden such use. Syrian air force helicopters have been filmed dropping chlorine barrel bombs on towns, pictures of spent Syrian-made chemical bombs and rockets are uploaded regularly to the internet, and Syria has sometimes allowed OPCW investigators to collect evidence which implicates the regime in chemical attacks. Indeed, the brazenness with which Assad has used chemical weapons is part of his strategy of demoralizing the opposition. Each time the regime uses banned weapons to attack civilians and the international community’s reaction is limited to denunciations and demarches, it sends a message to the opposition: “The Assad regime can get away with using the most barbaric weapons known to humanity and no one will protect you.” When the tough words of American and European leaders are not backed up by equally strong actions, they unwittingly reinforce the regime’s message of “Assad or we burn the country.”

The Kremlin’s use of a Novichok agent, first in Salisbury and now in Russia itself, appears to be part of a similar strategy of terrorizing opponents of the regime and deterring others from rising up to replace those killed or otherwise silenced. The parallels between Putin and Assad’s attitudes towards chemical weapons is not too surprising as Russia has had a front-row seat to Syria’s campaign of chemical weapon attacks since Russian military forces were deployed to support the Assad regime in September 2015. The Russian military coordinated extensively with the Syrian military during regime offensives against Aleppo in 2016 and Ghouta in 2018 that featured the heavy use of chemical weapons. Indeed, the United States has alleged that Russia’s involvement in these military operations constitutes a violation of the CWC’s prohibition against providing assistance or encouragement to other states to violate the treaty. While Vladimir Putin has sufficient experience using force, at home and abroad, that he did not need Assad’s mentorship in this regard, it appears that Assad’s ability to use chemical weapons so blatantly impressed and inspired Putin to follow suit in his own way.

Confronting the New Chemical Weapons Threat

U.S. policy-makers have long found it difficult to understand the motivations of their counterparts in authoritarian regimes. Such leaders, who rely heavily on coercive means to remain in power, are frequently more worried about internal threats to their regime than foreign threats. Western policy-makers are conditioned to think of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons as weapons of mass destruction and view them through the lens of national security. They too easily fall victim to mirror-imaging and assume that this is how other leaders view these weapons as well. While authoritarian leaders such as Putin, Assad, Kim Jong Un, Saddam Hussein, and P.W. Botha have valued the contribution of these types of weapons to national security, they have also considered these weapons, particularly chemical weapons, as tools to be used against domestic threats to the survival of their regime. Preventing Russia, or any other autocratic regime, from using poisons against domestic opponents is a tall order. When these regimes view dissidents and protestors as existential threats to the survival of the regime and their personal safety, there may not be sufficient carrots and sticks that outside powers can wield that would change their calculus. Understanding the motivations of authoritarian leaders, and the intensity of their concerns about regime security, however, is the first step towards devising an effective strategy for deterring their use of chemical, and possibly someday biological, weapons against their own people.

The use of chemical weapons was initially outlawed due to the horrific effects of these weapons on soldiers fighting on the battlefields of World War 1. More than one hundred years later, chemical weapons are still being used, but now against civilians demanding freedom, democracy, and human rights. While the ways in which the chemical weapons are being used have changed, there is an enduring need for the international community to condemn these barbaric weapons, hold accountable the perpetrators of such attacks, and deter future attacks.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gregory D. Koblentz is an associate professor and director of the Biodefense Graduate Program at the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University.