The resulting liver cell model will be a valuable tool for future studies on Ebola virus vital organ pathology and potential therapeutic interventions.

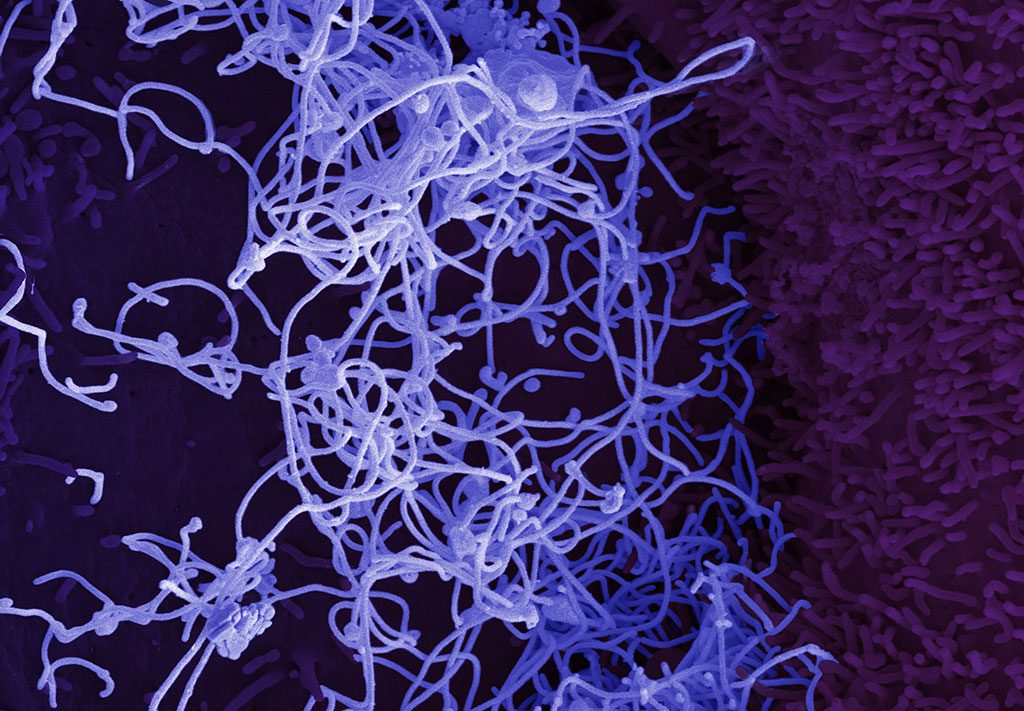

Ebola virus (EBOV) causes serious infections in humans and in fatal cases, damage and dysfunction of the liver is often present, suggesting that the liver plays a decisive role in disease outcome. Although the liver can become directly infected, it is not well understood how liver cells respond to the Ebola virus, and if liver injury is directly caused by the infection or secondary to other disease processes.

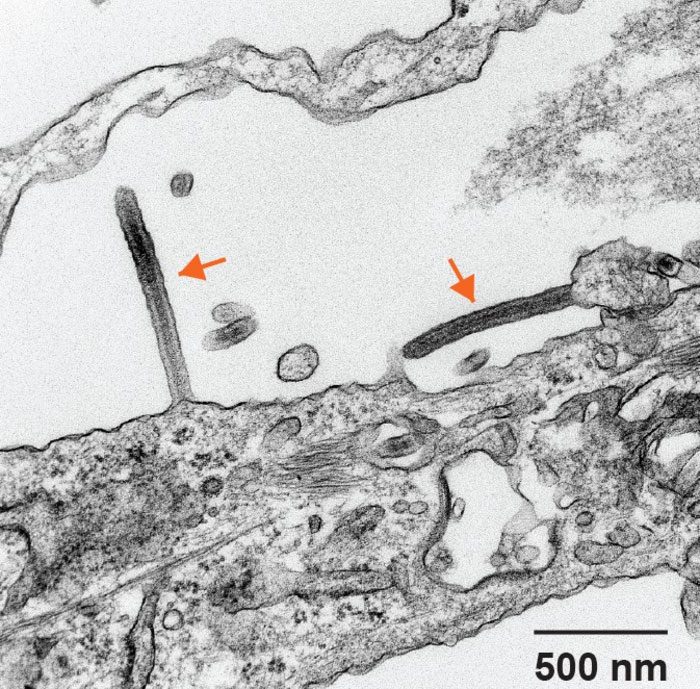

Research on liver cell response to Ebola virus infection has been limited by the lack of suitable cell-based models, however in a recent paper in Stem Cell Reports, Gustavo Mostoslavsky, Elke Mühlberger and colleagues have now harnessed stem cell biology to obtain and inexhaustible source of human liver cells, so-called hepatocyte-like cells (HCLs), derived from induced pluripotent stem cells. The stem cell-derived HLCs closely resembled primary liver cells and could be readily infected by Ebola virus in the lab.

Interestingly, the infected cultures were unable to mount a strong anti-inflammatory response to control viral spread, so that the majority of cells became infected over time. Although infected cells did not die, they did shut down genes required for proper HLC function, suggesting that viral infection directly disrupts liver function. Further, Ebola virus-infected immune cells could transfer the virus to HLCs in co-cultures, i.e. when cultured in the same dish, suggesting that infected immune cells may act as virus shuttles in patients.

“This is the first time such a platform (liver cells produced from stem cells) has been used to study Ebola virus infection. Our results provide first insights into the host response of primary human liver cells upon Ebola virus infection,” Mostoslavsky and Mühlberger said about the study. “Our study shows that major liver cell functions are compromised by Ebola virus infection. It also suggests that these highly pathogenic viruses have evolved a mechanism that prevents an early antiviral response in the infected organism. This gives them enough time to replicate and cause damage.”

The use of co-culture systems, such as the one highlighted in this study, can help determine which cell types in the liver are responsible for specific host responses, helping to define a cell-intrinsic disease signature that is difficult to discern in the whole-organ environment. The data presented corroborate that genes associated with liver function are perturbed in EBOV-infected hepatocytes. Future studies using this platform can help identify how EBOV impairs liver function during disease progression and inform the development of therapeutic interventions that may universally prevent EBOV fatality.

“Ebola virus outbreaks have a very high mortality and have a tremendous impact on healthcare. Understanding how the virus causes tissue damage is key to help design novel therapeutic interventions or prevent spread,” said Mostoslavsky and Mühlberger.

Twenty researchers participated in the study, including scientists from Boston University School of Medicine, the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL), Center for Regenerative Medicine (CReM), Boston Medical Center, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Disease, National Institutes of Health, Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Broad Institute, Department of Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Ebola virus infection induces a delayed type I IFN response in bystander cells and the shutdown of key liver genes in human iPSC-derived hepatocytes. Stem Cell Reports, 8 September 2022.