Recent decisions by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to reduce reliance on animal models in biomedical research reflect a major shift in policy and research ethics. While the goal of replacing animal use with alternative methods is widely supported, these moves risk outpacing the science. In critical domains such as pandemic preparedness and the development of medical countermeasures (MCMs) for chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) threats, the transition away from animal models could significantly delay or derail the availability of life-saving interventions.

Unlike routine drug development, MCM research often deals with rare, catastrophic events where human challenge trials are ethically impossible. For this reason, animal models remain an essential—often irreplaceable—tool in evaluating safety, efficacy, and dosage.

The Animal Rule: When Human Trials Aren’t an Option

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Animal Rule, established in 2002, allows for drug and biologic approvals based on efficacy data from animal studies when human trials are unethical or infeasible. These situations include exposure to high-consequence pathogens or toxins where no acceptable clinical trial model exists.

Under this framework, a sponsor must demonstrate:

- Efficacy in well-controlled animal studies

- Relevance of the animal model to human disease

- A clear understanding of pharmacokinetics to extrapolate an effective human dose

- Safety in humans through standard clinical trials

The Animal Rule is most often used for MCMs against bioterrorism agents and radiation injuries—threats for which it is impossible to conduct human efficacy trials. It has become the cornerstone of regulatory science in the CBRNE preparedness space.

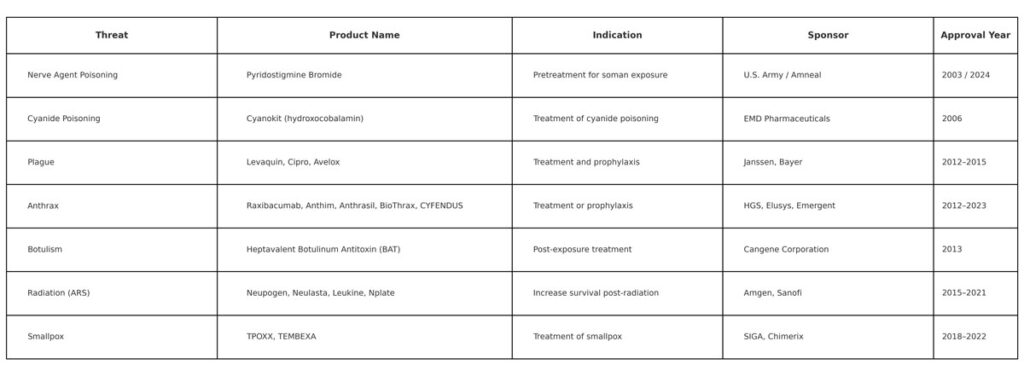

Medical Countermeasures Approved Under the Animal Rule

As of 2024, the FDA has approved 20 medical countermeasures under the Animal Rule—16 by the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) and 4 by the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER). These include therapies and vaccines for anthrax, smallpox, nerve agent poisoning, cyanide poisoning, botulism, plague, and acute radiation syndrome.

These MCMs were evaluated in animal models because challenge trials in humans would be unethical. Animal data remain the only viable route to establishing efficacy for these products. While in vitro and computational tools are advancing, they are not yet capable of replacing full biological systems in evaluating systemic effects, immune responses, or biodistribution.

FDA’s Supportive Infrastructure for Animal Rule Development

Recognizing the complexity of this regulatory pathway, the FDA has created a suite of guidance documents and programs to support product sponsors:

- Product Development Under the Animal Rule (2015)

- Anthrax, Smallpox, and Radiation Syndrome–specific development guidances

- Animal Model Qualification Program (AMQP) to reduce redundancy and enable model sharing

- Compliance Program for Nonclinical Labs (2019) to ensure integrity of animal study data

- SEND Data Standards to improve transparency and interoperability in animal rule submissions

The FDA strongly encourages early and ongoing engagement with sponsors and provides formal mechanisms for consultation to reduce regulatory uncertainty and improve efficiency.

A Premature Phase-Out: What’s at Risk

Efforts to reduce or phase out the use of animal models are gaining momentum across the U.S. federal research ecosystem, including NIH. However, in the context of CBRNE preparedness and pandemic response, this transition remains premature. As the 2022 GAO report (GAO-22-105248) notes, MCM developers already face substantial scientific and logistical hurdles. Removing animal models from the equation without fully validated alternatives will further slow progress and increase the risk of unpreparedness during an emergency.

Moreover, many of the current Animal Rule–approved products—like Raxibacumab, Cyanokit, or Neupogen—would not exist without in vivo efficacy data. The absence of these tools would leave the U.S. without proven interventions in scenarios ranging from nerve agent attacks to smallpox outbreaks.

Policy by Press Release: NIH’s Poorly Communicated Rollout Raises Broader Concerns

The NIH’s July 2025 announcement that it would no longer issue funding opportunities (NOFOs) exclusively for animal models has caused widespread confusion and concern within the biomedical research community. Delivered primarily through a workshop statement and a press release, the new policy was not accompanied by formal guidance, leaving researchers unsure about its scope, enforceability, and implications.

According to experts like Eliza Bliss-Moreau (UC Davis) and Arnold Kriegstein (UCSF), the lack of clarity on what counts as acceptable “new approach methodologies” (NAMs)—and whether traditional animal-based proposals will be disqualified—undermines both scientific rigor and operational planning. Researchers have also raised concerns about how NIH will financially and practically support the transition to alternative platforms, which remain immature in many fields.

In neuroscience, for example, mouse and non-human primate models remain essential for understanding brain circuitry, cognition, and disease. “If NAMs aren’t useful for select neuroscience experiments, labs could be wasting funding, time, and resources just to fulfill an NIH requirement,” says Bliss-Moreau. Others warn the current technology behind NAMs, such as organoids or AI-driven simulations, is still too simplistic to address complex, multi-system questions.

NIH has not published a finalized policy, and its internal review and feedback mechanisms for enforcing NAM inclusion remain undefined. This raises further concern about disconnected policymaking across federal research and regulatory agencies, particularly for programs—like those under the FDA’s Animal Rule—that depend on well-validated animal data.

Why It Matters: Public Health and National Security

Preparedness for CBRNE threats and emerging infectious diseases is not a niche concern—it is a public health imperative. Mass exposure to anthrax, botulinum toxin, or radioactive material could overwhelm hospitals, destabilize infrastructure, and create widespread panic.

The Strategic National Stockpile depends on MCMs developed under the Animal Rule to respond quickly to crises. Weakening the research infrastructure that enables these approvals threatens not only response capacity but also public confidence and national resilience.

The NIH’s move away from animal models has implications that extend far beyond the laboratory, directly affecting U.S. military readiness and frontline civilian response to CBRNE incidents. For the Department of Defense (DoD), animal-based research underpins the development of protective and therapeutic countermeasures essential to force protection—including pretreatments for nerve agents, radiation mitigators, and prophylactic vaccines for high-risk deployments. These tools are developed and validated through animal studies that simulate battlefield exposures or asymmetric threats, and are integrated into defense planning, battlefield medical protocols, and warfighter health strategies.

Similarly, civilian first responders, including paramedics, hazmat teams, and emergency physicians, rely on stockpiled MCMs developed under the Animal Rule to safely intervene during chemical spills, terrorist attacks, or large-scale biological releases. Without access to validated animal models, these products may never reach licensure—leaving both military and civilian operators more vulnerable.

Ethical Progress Must Align with Scientific Readiness

Modernizing biomedical research ethics is an important goal, but it must not compromise core public health capabilities. Animal models remain indispensable in the development of medical countermeasures for high-risk threats. Until alternative platforms can replicate the biological complexity required to evaluate such products, federal research policy must preserve—and even expand—support for animal-based research in this domain.

The stakes are too high for ideology to outpace science. For national security and global health preparedness, continuity in validated animal research is not optional—it is essential.

Sources and Further Reading

U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Animal Rule Approvals.

U.S. Government Accountability Office: Public Health Preparedness: Medical Countermeasure Development for Certain Serious or Life-Threatening Conditions.

The Transmitter: NIH proposal sows concerns over future of animal research, unnecessary costs.

National Association for Biomedical Research: NABR responds to FDA’s plan on reducing animal testing

Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents:Medical countermeasures for unwanted CBRN exposures: Part I chemical and biological threats with review of recent countermeasure patents.