A groundbreaking study published in The Lancet Microbe has identified a fast-spreading, drug-resistant bacterial strain that’s quietly gaining ground in hospitals and communities around the world. The study—led by scientists from Yangzhou University, Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital, and the University of Bath—focuses on Citrobacter freundii ST22, a clone that carries a dangerous array of antibiotic resistance genes, including those that disable last-resort treatments.

This international collaboration represents the most comprehensive effort yet to track the spread and evolution of carbapenemase-producing Citrobacter (CPC) species, particularly the high-risk ST22 clone. Using whole-genome sequencing of clinical isolates from a Chinese hospital alongside thousands of publicly available sequences, the researchers traced ST22’s emergence, resistance mechanisms, and global journey over centuries.

What They Found: A Rising High-Risk Clone

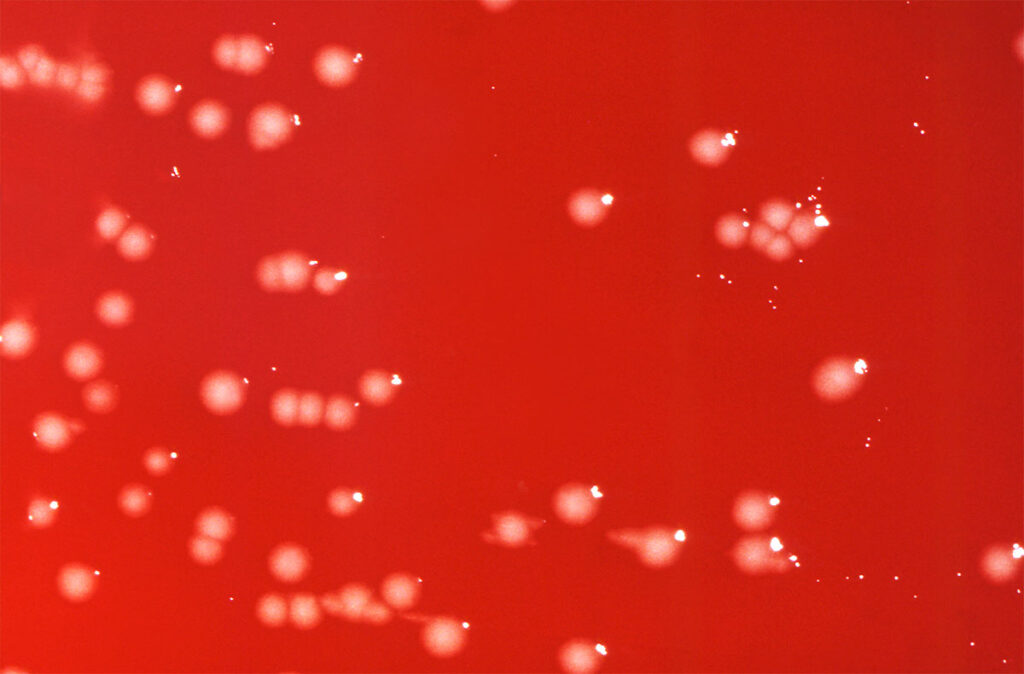

The researchers analyzed over 1,700 Citrobacter isolates from hospital patients in China, identifying 48 with resistance to carbapenems—a critical class of last-line antibiotics. Two species stood out: Citrobacter koseri and Citrobacter freundii. Among the latter, one clone—sequence type 22 (ST22)—was particularly alarming.

Key findings about ST22 include:

- Widespread presence: ST22 accounted for nearly one-third of all C. freundii genomes collected globally, appearing in hospitals, communities, and even environmental samples across 14 countries and six continents.

- Loaded with resistance genes: ST22 strains carried more antibiotic resistance genes than other Citrobacter types, including carbapenemase genes (like blaKPC, blaNDM, and blaIMP) and genes that resist even last-line drugs like tigecycline.

- Built to spread: These bacteria harbor multiple plasmids—mobile DNA elements that can transfer resistance genes to other bacteria—making ST22 highly adaptable and transmissible across bacterial species.

- Fast and fit: ST22 strains grew faster in laboratory tests than many other drug-resistant strains, including Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa—two common causes of hospital-acquired infections.

How It Spreads: Mobile DNA and Global Travel

The study traced the ST22 clone’s roots to the United States, where it likely emerged more than 300 years ago. Since then, it has moved across borders and continents through interconnected healthcare systems, patients, environmental reservoirs, and microbial ecosystems.

One of the main reasons ST22 is spreading so efficiently is its ability to carry and share plasmids that contain resistance genes. These plasmids often contain additional genetic elements like integrons and transposons, which accelerate gene transfer between bacteria.

The study found that:

- ST22 strains were especially rich in Inc-type plasmids, known for their wide host range.

- In laboratory transfer tests, 85% of the resistant Citrobacter strains could pass their resistance genes to E. coli—a strong indicator of real-world transmission risk.

- The plasmids identified in ST22 isolates closely resembled others found in different Enterobacterales species worldwide, suggesting frequent cross-species gene exchange.

Why This Matters

The emergence of high-risk clones like C. freundii ST22 isn’t just a problem for hospitals—it’s a growing challenge for health systems, governments, and the global community. These bacteria threaten to undermine the effectiveness of critical antibiotics, especially in intensive care units, transplant wards, and long-term care facilities.

From a national security perspective, ST22’s ability to move across borders and healthcare systems makes it a formidable pathogen. It has implications for:

- Public health preparedness, particularly around antimicrobial resistance (AMR) surveillance.

- Infection control policies, which must now adapt to faster-evolving, more transmissible resistance mechanisms.

- One Health coordination, as this strain has been found in environmental and potentially animal sources, reinforcing the need for integrated human-animal-environment health strategies.

If left unchecked, clones like ST22 could significantly limit treatment options for life-threatening infections and increase the risk of future AMR-driven outbreaks.

Next Steps for Health Professionals and Policymakers

This study is the first to comprehensively map the genomic evolution and global spread of CPC species, and it offers several urgent takeaways:

- Expand genomic surveillance of Citrobacter species in clinical and environmental settings.

- Implement targeted infection control protocols in healthcare facilities, especially where carbapenem-resistant organisms are emerging.

- Support research and innovation in new antimicrobial therapies, diagnostics, and AMR containment strategies.

- Foster international collaboration under the One Health framework to address reservoirs and transmission routes beyond hospitals.

Wang Q, Zhou L, Chen X, et al. Global emergence and transmission dynamics of carbapenemase-producing Citrobacter freundii sequence type 22 high-risk international clone: a retrospective, genomic, epidemiological study. Lancet Microbe. 16 July 2025.